Corfu

Native name: Κέρκυρα Nickname: Το νησί των Φαιάκων (The island of Faiakes) | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 39°36′N 19°52′E / 39.60°N 19.87°E |

| Area | 610.9 km2 (235.9 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 906 m (2972 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Administrative region | Ionian Islands |

| Regional unit | Corfu |

| Capital city | Corfu |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Corfiot, Corfiote |

| Population | 99,134 (2021) |

| Pop. density | 163.44/km2 (423.31/sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| • Summer (DST) | |

| Postal code | 490 81, 490 82, 490 83, 490 84, 491 31, 491 32 (former 491 00) |

| Area code(s) | 26610, 26620, 26630 |

| Official website | www |

Corfu (/kɔːrˈf(j)uː/ kor-FEW, -FOO, US also /ˈkɔːrf(j)uː/ KOR-few, -foo) or Kerkyra (Greek: Κέρκυρα, romanized: Kérkyra, pronounced [ˈcercira] )[a] is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands,[1] and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the nation's northwestern frontier.[2] The island is part of the Corfu regional unit, and is administered by three municipalities with the islands of Othonoi, Ereikoussa, and Mathraki.[3] The principal city of the island (pop. 32,095) is also named Corfu.[4] Corfu is home to the Ionian University.

The island is bound up with the history of Greece from the beginnings of Greek mythology, and is marked by numerous battles and conquests. Ancient Korkyra took part in the Battle of Sybota which was a catalyst for the Peloponnesian War, and, according to Thucydides, the largest naval battle between Greek city states until that time. Thucydides also reports that Korkyra, was one of the three great naval powers of fifth century BC Greece, along with Athens and Corinth.[5] Ruins of ancient Greek temples and other archaeological sites of the ancient city of Korkyra are located in Palaiopolis. Medieval castles punctuating strategic locations across the island are a legacy of struggles in the Middle Ages against invasions by pirates and the Ottomans. Two of these castles enclose its capital, which is the only city in Greece to be surrounded in such a way. As a result, Corfu's capital has been officially declared a Kastropolis ("castle city") by the Greek government.[6] From medieval times and into the 17th century, the island, as part of the Republic of Venice since 1204, successfully repulsed the Ottomans during several sieges, was recognised as a bulwark of the European States against the Ottoman Empire and became one of the most fortified places in Europe.[7] The fortifications of the island were used by the Venetians to defend against Ottoman intrusion into the Adriatic. In November 1815 Corfu came under British rule following the Napoleonic Wars, and in 1864 was ceded to modern Greece by the British government along with the remaining islands of the United States of the Ionian Islands under the Treaty of London. Corfu is the origin of the Ionian Academy, the first university of the modern Greek state, and the Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù, the first Greek theatre and opera house of modern Greece. The first governor of independent Greece after the revolution of 1821, founder of the modern Greek state, and distinguished European diplomat Ioannis Kapodistrias was born in Corfu.

In 2007, the city's old town was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, following a recommendation by ICOMOS.[8][9][10] The 1994 European Union summit was held in Corfu.[11] The island is a popular tourist destination.[12][13]

Name

[edit]The Greek name, Kerkyra or Korkyra, is related to two powerful water deities: Poseidon, god of the sea, and Asopos, an important Greek mainland river.[14] According to myth, Poseidon fell in love with the beautiful nymph Korkyra, daughter of Asopos and river nymph Metope, and abducted her.[14] Poseidon brought Korkyra to the hitherto unnamed island and, in marital bliss, offered her name to the place: Korkyra,[14] which gradually evolved to Kerkyra (Doric).[6] They had a child, Phaiax, after whom the inhabitants of the island were named Phaiakes (in Latin, Phaeaciani). Corfu is known as the island of the Phaeacians.

The name Corfù is a Venetian and Italian version of the Byzantine Κορυφώ (Koryphō), meaning "city of the peaks". It derives from the Byzantine Greek Κορυφαί (Koryphai) (crests or peaks), denoting the two peaks of Palaio Frourio.[6]

Geography

[edit]

The northeastern edge of Corfu lies off the coast of Sarandë, Albania, separated by straits varying in width from 3 to 23 km (2 to 14 miles). The southeast side of the island lies off the coast of Thesprotia, Greece. Its shape resembles a sickle (drepanē, δρεπάνι), to which it was compared by the ancients: the concave side, with the city and harbour of Corfu in the centre,[15] lies toward the Albanian coast. With the island's area estimated at 592.9 km2 (228.9 sq mi; 146,500 acres),[16] it runs approximately 64 km (40 mi) long, with greatest breadth at around 32 km (20 mi).

Two high and well-defined ranges divide the island into three districts, of which the northern is mountainous, the central undulating, and the southern low-lying. The more important of the two ranges, that of Pantokrator (Παντοκράτωρ – the Almighty) stretches east and west from Cape Falacro to Cape Psaromita, and attains its greatest elevation in the summit of the same name.[15]

The second range culminates in the mountain of Santi Jeca, or Santa Decca, as it is called by misinterpretation of the Greek designation Άγιοι Δέκα (Hagioi Deka), or the Ten Saints. The whole island, composed as it is of various limestone formations, presents great diversity of surface.[15] Beaches are found in Agios Gordis, the Korission Lagoon, Agios Georgios, Marathia, Kassiopi, Sidari, Palaiokastritsa and many others. Corfu is located near the Kefalonia geological fault formation; earthquakes have occurred.

Corfu's coastline spans 217 km (135 mi) including capes; its highest point is Mount Pantokrator (906 m (2,972 ft)); and the second Stravoskiadi, at 849 m (2,785 ft). The full extent of capes and promontories take in Agia Aikaterini, Drastis to the north, Lefkimmi and Asprokavos to the southeast, and Megachoro to the south. Two islands are also to be found at a middle point of Gouvia and Corfu Bay, which extends across much of the eastern shore of the island; are known as Lazareto and Ptychia (or Vido).

Diapontia Islands

[edit]

The Diapontia Islands (Greek: Διαπόντια νησιά) are located in the northwest of Corfu, (6 km away) and about 40 km (25 mi) from the Italian coast. The main islands are Othonoi, Ereikoussa and Mathraki.

Lazaretto Island

[edit]

Lazaretto Island, formerly known as St. Dimitrios, is located 1.1 km (0.68 mi) off the coast northeast of the city Corfu. Lazaretto has an area of 7.1 ha (17.5 acres) and comes under the administration of the Greek National Tourist Organization. During Venetian rule in the early 16th century, a monastery was built on the islet and a leprosarium established later in the century, after which the island was named. In 1798, during the French occupation, the islet was occupied by the Russo-Turkish fleet, who ran it as a military hospital. During the period of British rule, in 1814, the leprosarium was once again opened after renovations, and following Enosis in 1864 the leprosarium again saw occasional use.[17] During World War II, the Axis Occupation of Greece established a Nazi concentration camp there for the prisoners of the Greek Resistance movement,[18] while remaining today are the two-storeyed building that served as the Headquarters of the Italian army, a small church, and the wall against which those condemned to death were shot.[17][18]

Climate

[edit]Corfu has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa) featuring hot, dry summers and mild to cool, very rainy winters, which are much wetter than other Greek islands.[19] The highest temperature ever recorded is 42.8 °C (109.0 °F) on 24 July 2007 while the lowest is −6.0 °C (21.2 °F) on 17 January 2012.

| Climate data for Corfu (1955-2010) HNMS 1 m asl | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

42.8 (109.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.0 (21.2) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 135.8 (5.35) |

123.1 (4.85) |

99.6 (3.92) |

65.2 (2.57) |

36.5 (1.44) |

15.5 (0.61) |

8.7 (0.34) |

21.7 (0.85) |

87.8 (3.46) |

140.4 (5.53) |

187.1 (7.37) |

189.9 (7.48) |

1,111.3 (43.75) |

| Average rainy days | 14.8 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 12.2 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 7.4 | 11.4 | 14.7 | 16.5 | 122.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.6 | 74.1 | 73.1 | 72.5 | 69.2 | 63.2 | 61.7 | 61.7 | 70.3 | 74.9 | 77.5 | 77.1 | 70.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 117.7 | 116.8 | 116.0 | 206.5 | 276.8 | 324.2 | 364.5 | 332.8 | 257.1 | 188.9 | 133.5 | 110.9 | 2,545.7 |

| Source 1: InfoClimat extremes 1991-present [20]

Hellenic National Meteorological Service[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (extremes and sun 1961−1990)[22] | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity

[edit]Flora

[edit]Homer identifies six plants that adorn the garden of Alcinous: wild olive, pear, pomegranate, apple, fig and grape vine. Of these the apple and the pear are very inferior in Corfu; the others thrive, together with all the fruit trees known in Southern Europe, with addition of the kumquat, loquat and prickly pear and, in some spots, the banana. Olive trees dominate and their combination with cypress trees compose the typical Corfiot landscape. When undisturbed by cultivation,[15] the high maquis is the major natural vegetation type followed by deciduous oak forests and to a lesser extent, pine forests. In total more than 1800 plant species have been recorded.[23]

Fauna

[edit]Corfu is a continental island; its fauna is similar to that of the opposite mainland.

Birds

[edit]Avifauna is extensive, with around 300 bird species recorded since the 19th century. Species vary in size from the greater flamingo to the goldcrest.[24] Some species have become extinct, such as the rock partridge and the grey partridge, or no longer breed on the island, like the eastern imperial eagle, the white-tailed eagle, the Bonelli's eagle, the griffon vulture and the Egyptian vulture.[25][26]

Mammals

[edit]Around 40 species of mammals live on the island and in the sea around it. Fin whales, sperm whales, Cuvier's beaked whales, common bottlenose dolphins, short-beaked common dolphins, striped dolphins and Risso's dolphins are the regularly present cetaceans.[27] Monk seals appear from time to time without breeding there anymore. Eurasian otters still survive in the lagoons and streams of Corfu.[28][29][30] The golden jackal was very common till the 1960s, but after persecution it became extinct, with the last individuals observed in the first half of the 1990s.[31][32] Recent sightings indicate a recolonization effort from the nearby mainland.[29] Wild boars were exterminated after 2000, after farmers complained about crop damage, but at the moment they recolonized Corfu, swimming from the mainland.[29] Red foxes, beech martens, least weasels, European hares, northern white-breasted hedgehogs are quite widespread, as some of the smaller mammals like the European edible dormouse, the hazel dormouse, the house mouse, the yellow-necked mouse, the western broad-toothed field mouse, the wood mouse, the lesser white-toothed shrew, the etruscan shrew, as well as several species of bats.[29][33][34] Coypus, fallow deer, red deer, Indian crested porcupines, Siberian chipmunks and raccoons have been observed recently, but they are escapees and only the coypu and the raccoon have established viable populations.[35][29]

Amphibians and reptiles

[edit]Eight species of amphibians and 31 species of reptiles live or have been recorded on and around Corfu.[36]

The Greek newt, the Macedonian crested newt, the common toad, the European green toad, the European tree frog, the agile frog, the Epirus water frog and the Greek marsh frog are the representatives of the Amphibia Class.

Loggerhead sea turtles nest on the sandy beaches. On land, the Hermann's tortoise is widespread, while the marginated tortoise's status is unclear. In freshwater wetlands European pond terrapins and Balkan terrapins are common, but the last few years face the competition of the introduced pond slider.

Lizard species include typical lizards and geckos like the starred agama, the Mediterranean house gecko, the moorish gecko, the Dalmatian algyroides, the common wall lizard, the Balkan wall lizard, the Balkan green lizard, the European green lizard and the snake-eyed skink as also the legless Greek slow worm and the European glass lizard.

Of the snakes of Corfu, only the nose-horned viper is potentially dangerous. The harmless snake list includes the European worm snake, the javelin sand boa, the Dahl's whip snake, the Balkan whip snake, the Caspian whip snake, the four-lined snake, the Aesculapian snake, the leopard snake, the grass snake, the dice snake, the European cat snake, the eastern Montpellier snake.

Butterflies

[edit]There are 75 (plus) known species of Corfiot butterfly. Of particular interest are the southern swallowtail, southern festoon, Oberthür's grizzled skipper, Lulworth skipper, eastern orange tip, Krueper's small white, eastern baton blue and the tree grayling, many of which are of near threatened status. Before the turn of the century, not much had been published about the butterfly fauna of Corfu, and there were only a few short and obscure scientific articles. Recent interest grew when a Facebook discussion page (now called Corfu Butterfly Conservation) was created on 27th April 2014. Since that time, a group of responsible butterfly enthusiasts has grown (731 members at the time of writing) who share their passion for the butterflies and moths found on the island. It is through this work that more is being discovered about the distribution and abundance of butterflies across the island.[37]

Corfu Butterfly Conservation

[edit]Corfu Butterfly Conservation (CBC) was launched in April 2019. The group is composed of concerned residents, island visitors and scientists from throughout Europe.[38] Their goals are to produce robust scientific data that can be used to influence policy and protect habitat for the benefit of Corfu's butterflies and the wider natural environment, as well as to stimulate public interest in butterfly conservation.

CBC launched its website (www.corfubutterflyconservation.org, funded by the Royal Entomological Society's Goodman Award) on the 1 January 2021 to coincide with the launch of the Corfu Butterfly Survey.[39] The website describes the 75 species of butterflies that have been confirmed by members of CBC from the island. It outlines the value of butterflies as indicators of the island's biodiversity status and encourages enthusiasts to record their sightings on this website, as participants of the survey.[37] On the 16 December 2021, CBC became a UK registered community interest company (No.13813164) and so its identity changed from being a project to that of an organisation.[37]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The earliest reference to Corfu is the Mycenaean Greek word ko-ro-ku-ra-i-jo ("man from Kerkyra") written in Linear B syllabic script, c. 1300 BC.[40] According to Strabo, Corcyra (Κόρκυρα) was the Homeric island of Scheria (Σχερία),[41] and its earliest inhabitants were the Phaeacians (Φαίακες). The island has indeed been identified by some scholars with Scheria, the island of the Phaeacians described in Homer's Odyssey, though conclusive and irrefutable evidence for this theory has not been found. Apollonius of Rhodes depicts the island in Argonautica as a place visited by the Argonauts. Jason and Medea were married there in 'Medea's Cave'. Apollonius named the island Drepane, Greek for "sickle", since it was thought to hide the sickle that Cronus used to castrate his father Uranus, from whose blood the Phaeacians were descended. In an alternative account, Apollonius identifies the buried sickle as a scythe belonging to Demeter, yet the name Drepane probably originated in the sickle-shape of the island. According to a scholiast, commenting on the passage in Argonautica, the island was first of all called Macris after the nurse of Dionysus who fled there from Euboea.[42]

Some scholars have asserted that Corfu is Taphos, the island of the Lelegian Taphians.[43]

According to Strabo (VI, 269), the Liburnians were masters of the island Korkyra (Corfu) for a time, until the 8th century BC. They reportedly were expelled from Korkyra by the Corinthians.[44][45][46]

At a date no doubt previous to the foundation of Syracuse, Corfu was peopled by settlers from Corinth, probably 730 BC, but it appears to have previously received a stream of emigrants from Eretria. The commercially advantageous location of Corcyra on the way between Greece and Magna Grecia, and its fertile lowlands in the southern section of the island favoured its growth and, influenced perhaps by the presence of non-Corinthian settlers, its people, quite contrary to the usual practice of Corinthian colonies, maintained an independent and even hostile attitude towards the mother city.[15]

This opposition came to a head in the early part of the 7th century BC, when their fleets fought the first naval battle recorded in Greek history: 665 BC according to Thucydides. These hostilities ended in the conquest of Corcyra by the Corinthian tyrant Periander (Περίανδρος) who induced his new subjects to join in the colonization of Apollonia and Anactorium. The island soon regained its independence and thenceforth devoted itself to a purely mercantile policy. During the Persian invasion of 480 BC it manned the second largest Greek fleet (60 ships), but took no active part in the war. In 435 BC it was again involved in a quarrel with Corinth over the control of Epidamnus, and sought assistance from Athens (see Battle of Sybota).[15]

This new alliance was one of the chief immediate causes of the Peloponnesian War, in which Corcyra was of considerable use to the Athenians as a naval station, but did not render much assistance with its fleet. The island was nearly lost to Athens by two attempts of the oligarchic faction to effect a revolution; on each occasion the popular party ultimately won the day and took a most bloody revenge on its opponents (427 BC and 425 BC).[47][15]

During the Sicilian campaigns of Athens Corcyra served as a supply base; after a third abortive rising of the oligarchs in 410 BC it practically withdrew from the war. In 375 BC it again joined the Athenian alliance; two years later it was besieged by a Spartan force, but in spite of the devastation of its flourishing countryside held out successfully until relieved. In the Hellenistic period Corcyra was exposed to attack from several sides.[15]

In 303 BC, after a vain siege by Cassander,[15] the island was occupied for a short time by the Lacedaemonian general Cleonymus of Sparta, then regained its independence and later it was attacked and conquered by Agathocles of Syracuse. He offered Corfu as dowry to his daughter Lanassa on her marriage to Pyrrhus, King of Epirus. The island then became a member of the Epirotic alliance. It was then perhaps that the settlement of Cassiope was founded to serve as a base for the King of Epirus' expeditions. The island remained in the Epirotic alliance until 255 BC when it became independent after the death of Alexander, last King of Epirus. In 229 BC, following the naval battle of Paxos, it was captured by the Illyrians, but was speedily delivered by a Roman fleet and remained a Roman naval station until at least 189 BC. At this time, it was governed by a prefect (presumably nominated by the consuls), but in 148 BC it was attached to the province of Macedonia.[48] In 31 BC, it served Octavian (Augustus) as a base against Mark Antony.[15]

Roman and medieval history

[edit]

Christianity arrived in Corfu early; two disciples of Saint Paul, Jason of Tarsus and Sosipatrus of Patras, taught the Gospel, and according to tradition the city of Corfu and much of the island converted to Christianity. Their relics were housed in the old cathedral (at the site of the current Old Fortress, before a dedicated church was built for them c. 100 AD.[49]

During Late Antiquity (late Roman/early Byzantine period), the island formed part of the province of Epirus Vetus in the praetorian prefecture of Illyricum.[50] In 551, during the Gothic War, the Ostrogoths raided the island and destroyed the city of Corfu, then known as Chersoupolis (Χερσούπολις, "city on the promontory") because of its location between Garitsa Bay and Kanoni. Over the next centuries, the main settlement was moved north, to the location of the current Old Fortress, where the rocky hills offered natural protection against raids. From the twin peaks of the new site, the medieval city received its new name, Korypho (Κορυφώ, "city on the peak") or Korphoi (Κορφοί, "peaks"), whence the modern Western name of "Corfu". The previous site of the city, now known as Palaiopolis (Παλαιόπολις, "old city"), continued to be inhabited for several centuries, however.[51]

From at least the early 9th century, Corfu and the other Ionian Islands formed part of the theme of Cephallenia.[52] This naval theme provided a defensive bulwark for Byzantium against western threats, but also played a major role in securing the sealanes to the Byzantine possessions in southern Italy. Indeed, traveller reports from throughout the middle Byzantine period (8th–12th centuries) make clear that Corfu was "an important staging post for travels between East and West".[53] Indeed, the medieval name of Corfu first appears (Latinized Coryphus) in Liutprand of Cremona's account of his 968 embassy to the Byzantine court.[54] Corfu enjoyed relative peace and safety during the Macedonian dynasty (867–1054), which allowed the construction of a monumental church to Saints Iason and Sosipatrus outside the city wall of Palaiopolis.[54] Nevertheless, in 933, the city, led by its archbishop, Arsenios, withstood a Saracen attack; Arsenios was canonized and became the city's patron saint.[55]

The peace and prosperity of the Macedonian era ended with another Saracen attack in 1033, but more importantly with the emergence of a new threat: following the Norman conquest of Southern Italy, the ambitious Norman monarchs set their sights on expansion in the East. Three times on the space of a century Corfu was the first target and served as a staging area for the Norman invasions of Byzantium. The first Norman occupation from 1081 to 1084 was ended only after the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos secured the aid of the Republic of Venice, in exchange to wide-ranging commercial concessions to Venetian merchants. The admiral George of Antioch captured Corfu again in 1147, and it took a ten-month siege for Manuel I Komnenos to recover the island in 1149. In the third invasion in 1185, the island was again captured by William II of Sicily, but was soon regained by Isaac II Angelos.[56]

During the break-up of the Byzantine Empire the island was occupied by Genoese privateers (1197–1207), who in turn were expelled by the Venetians. In 1214 it passed to the Greek despots of Epirus,[15] who gave it to Manfred of Sicily as a dowry in 1259.[57] At his death in 1267 it passed to the House of Anjou. Thus, Corfu became a part of the Angevin Kingdom of Albania that was established and ruled by Frankish Charles of Anjou of the royal Capetian dynasty.[58] Under the latter, the island suffered considerably from the inroads of various adventurers.[15]

The island was one of the first places in Europe in which Romani people settled. In about 1360, a fiefdom, called the Feudum Acinganorum was established, with mainly Romani serfs.[59][60] From 1386, Corfu was controlled by the Republic of Venice, which in 1401 acquired formal sovereignty and retained it until the French Occupation of 1797.[15] Corfu became central for the propagation of the activities of the Filiki Etaireia among the Greek Diaspora and philhellenic societies across Europe, through nobles like Ioannis Kapodistrias and Dionysios Romas.

Venetian rule

[edit]

From medieval times and into the 17th century, the island was recognised as a bulwark of the European States against the Ottoman Empire and became one of the most fortified places in Europe.[7] The fortifications of the island were used by the Venetians to defend against Ottoman intrusion into the Adriatic. Corfu repulsed several Ottoman sieges, before passing under British rule following the Napoleonic Wars.[61][62][63][64][65][66][67]

Kerkyra, the "Door of Venice" during the centuries when the whole Adriatic was the Gulf of Venice,[68] remained in Venetian hands from 1401 until 1797, though several times assailed by Ottoman naval and land forces[15] and subjected to four notable sieges in 1537, 1571, 1573 and 1716, in which the strength of the city defences asserted itself time after time. The effectiveness of the powerful Venetian fortifications as well as the strength of some old Byzantine castles in Angelokastro, Kassiopi Castle, Gardiki and elsewhere, were additional factors that enabled Corfu to remain free. Will Durant claimed that Corfu owed to the Republic of Venice the fact that it was one of the few parts of Greece never conquered by the Ottomans.[69]

A series of attempts by the Ottomans to take the island began in 1431 when Ottoman troops under Ali Bey landed on the island. The Ottomans tried to take the city castle and raided the surrounding area, but were repulsed.[70]

The Siege of Corfu (1537) was the first great siege by the Ottomans. It began on 29 August 1537, with 25,000 soldiers from the Ottoman fleet landing and pillaging the island and taking 20,000 hostages as slaves. Despite the destruction wrought on the countryside, the city castle held out in spite of repeated attempts over twelve days to take it, and the Turks left the island unsuccessfully because of poor logistics and an epidemic that decimated their ranks.[70]

Thirty-four years later, in August 1571, Ottoman forces returned for yet another attempt to conquer the island. Having seized Parga and Mourtos from the Greek mainland side, they attacked the Paxi islands. Subsequently they landed on Corfu's southeast shore and established a large beachhead all the way from the southern tip of the island at Lefkimi to Ipsos in Corfu's eastern midsection. These areas were thoroughly pillaged as in past encounters. Nevertheless the city castle stood firm again, a testament to Corfiot-Venetian steadfastness as well as the Venetian castle-building engineering skills. Another castle, Angelokastro, situated on the northwest coast near Palaiokastritsa (Greek: Παλαιοκαστρίτσα meaning Old Castle place) and located on particularly steep and rocky terrain, also held out. The castle is a tourist attraction today.[70]

These defeats in the east and the west of the island proved decisive, and the Ottomans abandoned their siege and departed. Two years later they repeated their attempt. Coming from Africa after a victorious campaign, they landed in Corfu and wreaked havoc on rural areas. Following a counterattack by the Venetian-Corfiot forces, the Ottoman troops were forced to leave the city sailing away.[70]

The second great siege of Corfu took place in 1716, during the last Ottoman–Venetian War (1714–18). After the conquest of the Peloponnese in 1715, the Ottoman fleet appeared in Buthrotum opposite Corfu. On 8 July the Ottoman fleet, carrying 33,000 men, sailed to Corfu from Buthrotum and established a beachhead at Ipsos.[70] The same day, the Venetian fleet encountered the Ottoman fleet off the Corfu Channel and defeated it in the ensuing naval battle. On 19 July, after taking a few outlying forts, the Ottoman army reached the hills around the city of Corfu and laid siege to it. Despite repeated assaults and heavy fighting, the Ottomans were unable to breach the defences and were forced to raise the siege after 22 days. The 5,000 Venetians and foreign mercenaries, together with 3,000 Corfiotes, under the leadership of Count von der Schulenburg who commanded the defence of the island, were victorious once more.[6][70][71] The success was owed in no small part to the extensive fortifications, where Venetian castle engineering had proven itself once again against considerable odds. The repulse of the Ottomans was widely celebrated in Europe, Corfu being seen as a bastion of Western civilization against the Ottoman tide.[61][72] Today, however, this role is often relatively unknown or ignored, but was celebrated in Juditha triumphans by the Venetian composer Antonio Vivaldi.

Venetian policies and legacy

[edit]Corfu's urban architecture differs from that of other major Greek cities, because of Corfu's unique history. From 1386 to 1797, Corfu was ruled by Venetian nobility; much of the city reflects this era when the island belonged to the Republic of Venice, with multi-storeyed buildings on narrow lanes. The Old Town of Corfu has clear Venetian influence and is amongst the World Heritage Sites in Greece. It was in the Venetian period that the city saw the erection of the first opera house (Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù) in Greece.

Many Venetian-speaking families settled in Corfu during these centuries; they were called Corfiot Italians, and until the second half of the 20th century the Veneto da mar was spoken in Corfu. During this time, the local Greek language assimilated a large number of Italian and Venetian words, many of which are still common today. The internationally renowned Venetian-born British photographer Felice Beato (1832–1909) is thought to have spent much of his childhood in Corfu. Also many Italian Jews took refuge in Corfu during the Venetian centuries and spoke their own language (Italkian), a mixture of Hebrew-Italian in a Venetian or Apulian dialect with some Greek words.

Venetians promoted the Catholic Church during their four centuries of rule in Corfu. Today the majority of Corfiots are Greek Orthodox, but the small Catholic minority (5%), living harmoniously with the Orthodox community, owes its faith to these origins. These contemporary Catholics are mostly families who came from Malta, but also from Italy, and today the Catholic community numbers about 4,000 (2⁄3 of Maltese descent), who live almost exclusively in the Venetian "Citadel" of Corfu City. Like other native Greek Catholics, they celebrate Easter using the same calendar as the Greek Orthodox church. The Cathedral of St. James and St. Christopher in Corfu City is the see of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Corfu, Zakynthos and Cephalonia.

The island served also as a refuge for Greek scholars, and in 1732, it became the home of the first academy of modern Greece.[15] A Corfu cleric and scholar, Nikephoros Theotokis (1732–1800) became renowned in Greece as an educator, and in Russia (where he moved later in his life) as an Orthodox archbishop.

The island's culture absorbed Venetian influence in a variety of ways; like other Ionian islands (see Cuisine of the Ionian islands), its local cuisine took in such elements and today's Corfiot cooking includes Venetian delicacies and recipes: "Pastitsada", deriving from the Venetian "Pastissada" (Italian: "Spezzatino") and the most popular dish in the island of Corfu, "Sofrito", "Strapatsada", "Savoro", "Bianco" and "Mandolato".

-

Venetian Old Fortress, Map 1573

-

Panoramic view of Corfu (city) from the New Fortress

-

Detail of the south wing of the entrance at Kassiopi Castle

-

View of Kasiopi village from the castle

19th century

[edit]

By the 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio, Corfu was ceded to the French, who occupied it for two years as the département of Corcyre, until they were expelled by a joint Russian-Ottoman squadron under Admiral Ushakov. For a short time it became the capital of a self-governing federation of the Heptanesos ("Seven Islands"), under Ottoman suzerainty; in 1807 after the Treaty of Tilsit its faction-ridden government was again replaced by a French administration under governor François-Xavier Donzelot, and in 1809 it was besieged in vain by a British Royal Navy fleet, which had captured all the other Ionian islands.[15]

Following the final defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, the Ionian Islands became a protectorate of the United Kingdom by the Treaty of Paris of 5 November 1815 as the United States of the Ionian Islands. Corfu became the seat of the British Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands.[15] The period of British rule led to investment in new roads, an improved water supply system, and the expansion of the Ionian Academy into a university. During this period the Greek language became the official language.[citation needed]

Following a plebiscite the Second National Assembly of the Greeks at Athens elected a new king, Prince Wilhelm (William) of Denmark, who took the name George I and brought with him the Ionian Islands as a coronation gift from Britain. On 29 March 1864, the United Kingdom, Greece, France and Russia signed the Treaty of London, pledging the transfer of sovereignty to Greece upon ratification. Thus, on 21 May, by proclamation of the Lord High Commissioner, the Ionian Islands were united with Greece.[70]

British Lord High Commissioners during the protectorate

[edit]

This is a list of the British High Commissioners of the Ionian Islands; (as well as the transitional Greek Governor, appointed a year prior to Enosis (Union) with Greece in 1864).[73]

- Sir James Campbell 1814–1816

- Sir Thomas Maitland (1759–1824) 1815–1823

- Sir Frederick Adam (1781–1853) 1823–1832

- Sir Alexander Woodford (1782–1870) 1832

- George Nugent-Grenville, 2nd Baron Nugent (1788–1850) 1832–1835

- Howard Douglas (1776–1861) 1835–1840

- James Alexander Stewart-Mackenzie (1784–1843) 1840–1843

- John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton (1778–1863) 1843–1849

- Sir Henry George Ward (1797–1860) 1849–1855

- Sir John Young (1807–1876) 1855–1859

- William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898) 1859

- Sir Henry Knight Storks (1811–1874) 1859–1863

- Count Dimitrios Nikolaou Karousos, President of the Ionian Parliament (1799–1873) 1863–1864

In 1891, an anti-Semitic pogrom[74] took place to oppose Jewish participation in elections.[75] Later, blood libel caused riots,[76] it lasted three weeks and some 22 Jews died.[77] A part of the Jewish population preferred to leave the island, mainly for Thessaloniki, the Ottoman territories being more welcoming. It was following these events that Albert Cohen's family settled in Marseille.[78]

First World War

[edit]

During the First World War, the island served as a refuge for the Serbian army that retreated there on Allied forces' ships from a homeland occupied by the Austrians, Germans and Bulgarians. During their stay, a large portion of Serbian soldiers died from exhaustion, food shortage, and various diseases. Most of their remains were buried at sea near the island of Vido, a small island at the mouth of Corfu port, and a monument of thanks to the Greek nation has been erected at Vido by the grateful Serbs; consequently, the waters around Vido Island are known by the Serbian people as the Blue Tomb (in Serbian, Плава Гробница, Plava Grobnica), after a poem written by Milutin Bojić following World War I.[79]

Interwar period

[edit]In 1923, after a diplomatic dispute between Italy and Greece, Italian forces bombarded and occupied Corfu. The League of Nations settled this Corfu incident in Italy's favour.

Second World War

[edit]Italian occupation and resistance

[edit]

During the Greco-Italian War, Corfu was occupied by the Italians in April 1941. They administered Corfu and the Ionian islands as a separate entity from Greece until September 1943, following Benito Mussolini's orders of fulfilling Italian Irredentism and making Corfu part of the Kingdom of Italy. During the Second World War the 10th Infantry Regiment of the Greek Army, composed mainly of Corfiot soldiers,[80] was assigned the task of defending Corfu. The regiment took part in Operation Latzides, which was a unsuccessful attempt to stem the forces of the Italians.[80] After Greece's surrender to the Axis, the island came under Italian control and occupation.[80] On the first Sunday of November 1941, high school students from all over Corfu took part in student protests against the occupying Italian army; these student protests of the island were among the first acts of overt popular Resistance in occupied Greece and a rare phenomenon even by wartime European standards.[80] Subsequently, a considerable number of Corfiots escaped to Epirus in mainland Greece and enlisted as partisans in ELAS and EDES, in order to join the resistance movement gathering in the mainland.[80]

German bombing and occupation

[edit]

Upon the fall of Italian fascism in 1943, the Nazis moved to take control of the island. On 14 September 1943, Corfu was bombarded by the Luftwaffe. The Nazi bombing raids destroyed most of the city's buildings, including churches, homes, and whole city blocks, especially in the Jewish quarter Evraiki. Other losses included the city's market (αγορά) and the hotel Bella Venezia. The worst losses were the historic buildings of the Ionian Academy (Ιόνιος Ακαδημία), the Municipal Theatre (which in 1901 had replaced the Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù), the Municipal Library, and the Ionian Parliament.[80]

Following the Wehrmacht invasion, the Italians capitulated, and the island came under German occupation. Corfu's mayor at the time, Kollas, was a known collaborator and various anti-semitic laws were passed by the Nazi occupation government of the island.[81] In early June 1944, while the Allies bombed Corfu as a diversion from the Normandy landings, the Gestapo rounded up the Jews of the city, temporarily incarcerated them at the old fort (Palaio Frourio), and on 10 June sent them to Auschwitz II, where most of them were murdered by gas.[81][82] Approximately two hundred out of a total population of 1,900 escaped.[83] Many among the local population at the time provided shelter and refuge to those 200 Jews who managed to escape the Nazis.[84] In Evraiki (Εβραική, meaning Jewish quarter), there is currently a synagogue with about 65 members, who still speak their original Italkian language.[83]

Liberation

[edit]

Corfu was liberated by British troops, specifically the 40th Royal Marine Commando, which landed in Corfu on 14 October 1944, as the Germans were evacuating Greece.[85] The Royal Navy swept the Corfu Channel for mines in 1944 and 1945, and found it to be free of mines.[86] A large minefield was laid there shortly afterwards by the newly communist Albania and gave rise to the Corfu Channel Incident.[86][87][88][89] This incident led to the Corfu Channel Case, where the United Kingdom opened a case against the People's Republic of Albania at the International Court of Justice.[90][91]

Post–World War and modern Corfu

[edit]After World War II and the Greek Civil War, the island was rebuilt under the general programme of reconstruction of the Greek Government (Ανοικοδόμησις) and many elements of its classical architecture remain. Its economy grew but a portion of its inhabitants left the island for other parts of the country; buildings erected during Italian occupation – such as schools or government buildings – were put back to civic use. In 1956 Maria Desylla Kapodistria, relative of first Governor (head of state) of Greece Ioannis Kapodistrias, was elected mayor of Corfu and became the first female mayor in Greece.[92] The Corfu General Hospital was also constructed;[93] electricity was introduced to the villages in the 1950s, the radio substation of Hellenic Radio in Corfu was inaugurated in March 1957,[94] and television was introduced in the 1960s, with internet connections in 1995.[95] The Ionian University was established in 1984.

Architecture

[edit]

Venetian influence

[edit]

Corfu's urban architecture influence derives from Venice, reflecting the fact that from 1386 to 1797 the island was ruled by the Venetians. The architecture of the Old Town of Corfu along with its narrow streets, the kantounia, has clear Venetian influence and is amongst the World Heritage Sites in Greece. Other notable Venetian-era buildings include the Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù, the first Greek opera house, and Liston, a multi-level commercial and residential building, with an arched colonnade at ground level, lined with cafes and restaurants on its east side, and restaurants and other stores on its west side. Liston's main thoroughfare is often the site of parades and other mass gatherings. Liston is on the edge of the Spianada (Esplanade), the vast main plaza and park which incorporates a cricket field, a pavilion, and Maitland's monument. Also notable are the Old and New forts, the recently restored Palace of Sts. Michael and George, formerly the residence of the British colonial governor and the seat of the Ionian Senate, and the summer Palace of Mon Repos, formerly the property of the Greek royal family and birthplace of the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. The Park of Mon Repos is built on part of the Palaiopolis of Kerkyra, where excavations were conducted by the Greek Archaeological Service in collaboration with academics and universities internationally. Examples of the finds can be found in the Museum of the Palace of Mon Repos and at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu.[96]

The Achilleion

[edit]

In 1889, Empress Elisabeth of Austria built a summer palace in the region of Gastouri (Γαστούρι) to the south of the city, naming it Achílleion (Αχίλλειον) after the Homeric hero Achilles. The structure is filled with paintings and statues of Achilles, both in the main hall and in the gardens, depicting scenes of the Trojan War. The palace, with the neoclassical Greek statues that surround it, is a monument to platonic romanticism as well as escapism. It served as a refuge for the grieving Empress following the tragic death of her only son Crown Prince, Rudolf.

The Imperial gardens on the hill look over the surrounding green hills and valleys and the Ionian Sea. The centrepiece of the gardens is a marble statue on a high pedestal, of the mortally wounded Achilles (Greek: Αχιλλεύς Θνήσκων, Achilleús Thnēskōn, Achilles Dying) without hubris and wearing only a simple cloth and an ancient Greek hoplite helmet. This statue was carved by German sculptor Ernst Gustav Herter.

The hero is presented devoid of rank or status, and seems notably human, though heroic, as he is forever trying to pull Paris's arrow from his heel. His classically depicted face is full of pain. He gazes skyward, as if to seek help from Olympus. According to Greek mythology, his mother Thetis was a goddess.[citation needed]

In contrast, at the great staircase in the main hall is a giant painting of the triumphant Achilles full of pride. Dressed in full royal military regalia and erect on his racing chariot, he pulls the lifeless body of Hector of Troy in front of the stunned crowd watching helplessly from inside the walls of the Trojan citadel.

In 1898, Empress Sissi was assassinated at the age of 60 by an Italian anarchist, Luigi Lucheni, in Geneva, Switzerland. After her death, the palace was sold to the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. Following the Kaiser's purchase of the Achilleion, he invited archaeologist Reinhard Kekulé von Stradonitz, a friend and advisor, to come to Corfu to advise him where to position the huge statue of Achilles which he commissioned. The famous salute to Achilles from the Kaiser, which had been inscribed at the statue's base, was also created by Kekulé. The inscription read:[97]

To the Greatest Greek from the Greatest German

The inscription was subsequently removed after World War II.[98]

The Achilleion was eventually acquired by the Greek state and has now been converted into a museum.

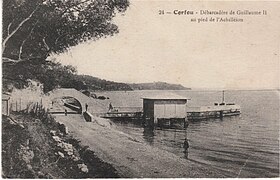

Kaiser's Bridge

[edit]

German Kaiser Wilhelm II was also fond of taking holidays in Corfu. Having purchased the Achilleion in 1907 after Sissi's death, he appointed Carl Ludwig Sprenger as the botanical architect of the Palace, and also built a bridge later named by the locals after him—the "Kaiser's bridge" (Greek: η γέφυρα του Κάιζερ transliterated as: i gefyra tou Kaizer)—to access the beach without traversing the road forming the island's main artery to the south. The bridge, arching over the road, spanned the distance between the lower gardens of Achilleion and the nearby beach; its remains are an important landmark on the highway. The bridge's central section was demolished by the Wehrmacht in 1944, during the German occupation of World War II, to allow for the passage of an enormous cannon, forming part of the Nazi defences in the southeastern coast of Corfu.[99][100]

Urban landscape

[edit]Old town

[edit]The Old Town of Corfu city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In several parts of the old city, buildings of the Venetian era are to be found. The old city's architectural character is strongly influenced by the Venetian style, coming as it did under Venetian rule for a long period; its small and ancient side streets, and the old buildings' trademark arches are particularly reminiscent of Venice.

The city of Corfu stands on the broad part of a peninsula, whose termination in the Venetian citadel (Greek: Παλαιό Φρούριο) is cut off from it by an artificial fosse formed in a natural gully, with a seawater moat at the bottom,[15] that now serves as a marina and is called the Contrafossa. In the old town there are many narrow streets paved with cobblestones. These streets are known as kantoúnia (Greek: καντούνια), and the older amongst them sometimes follow the gentle irregularities of the ground; while many are too narrow for vehicular traffic. A promenade rises by the seashore towards the bay of Garitsa (Γαρίτσα), together with an esplanade between the city and the citadel known as Spianada with the Liston arcade (Greek: Λιστόν) to its west side, where restaurants and bistros abound.[1]

Ano and Kato Plateia and the music pavilion

[edit]

Near the old Venetian Citadel a large square called Spianada is also to be found, divided by a street in two parts: "Ano Plateia" (literally: "Upper square") and "Kato Plateia" (literally: "Lower square"), (Ανω Πλατεία and Κάτω Πλατεία in Greek). This is the biggest square in South-Eastern Europe and one of the largest in Europe,[101][102] and replete with green spaces and interesting structures, such as a Roman-style rotunda from the era of British administration, known as the Maitland monument, built to commemorate Sir Thomas Maitland. An ornate music pavilion is also present, where the local "Philharmonikes" (Philharmonic Orchestras) (Φιλαρμονικές), mount classical performances in the artistic and musical tradition for which the island is well known. "Kato Plateia" also serves as a venue where cricket matches are held from time to time. In Greece, cricket is unique to Corfu, as it was once a British protectorate.

Palaia Anaktora and its gardens

[edit]

Just to the north of "Kato Plateia" lie the "Palaia Anaktora" (Παλαιά Ανάκτορα: literally "Old Palaces"): a large complex of buildings of Roman architectural style which formerly housed the Kings of Greece, and prior to that the British Governors of the island. It was then called the Palace of Saints Michael and George. The Order of St. Michael and St. George was founded here in 1818 with motto auspicium melioris aevi,[103][104] and is still awarded by the United Kingdom. Today the palace is open to the public and forms a complex of halls and buildings housing art exhibits, including a Museum of Asian Art, unique across Southern Europe in its scope and in the richness of its Chinese and Asian exhibits. The gardens of the Palaces, complete with old Venetian stone aquariums, exotic trees and flowers, overlook the bay through old Venetian fortifications and turrets, and the local sea baths (Μπάνια τ' Αλέκου) are at the foot of the fortifications surrounding the gardens. A café on the grounds includes its own art gallery, with exhibitions of both local and international artists, known locally as the Art Café. From the same spot, the viewer can observe ships passing through the narrow channel of the historic Vido island (Νησί Βίδου) to the north, on their way to Corfu harbour (Νέο Λιμάνι), with high speed retractable aerofoil ferries from Igoumenitsa also cutting across the panorama. A wrought-iron aerial staircase, closed to visitors, descends to the sea from the gardens; the Greek royal family used it as a shortcut to the baths. Rewriting history, locals now refer to the old Royal Gardens as the "Garden of the People" (Ο Κήπος του Λαού).

Churches

[edit]In the city, there are thirty-seven Greek churches, the most important of which are the city's cathedral, the church dedicated to Our Lady of the Cave (η Παναγία Σπηλιώτισσα (hē Panagia Spēliōtissa)); Saint Spyridon Church, wherein lies the preserved body of the patron saint of the island; and finally the suburban church of St Jason and St Sosipater (Αγιοι Ιάσων και Σωσίπατρος), reputedly the oldest in the island,[15] and named after the two saints probably the first to preach Christianity to the Corfiots.

Pontikonisi

[edit]The nearby island, known as Pontikonisi (Greek meaning "mouse island"), though small is very green with abundant trees, and at its highest natural elevation (excluding its trees or man-made structures, such as the monastery), stands at about 2 m (6 ft 6.74 in). Pontikonisi is home of the monastery of Pantokrator (Μοναστήρι του Παντοκράτορος); the white stone staircase of the monastery, viewed from afar, gives the impression of a (mouse) tail, which lent the island its name.

Archaeology

[edit]Palaiopolis

[edit]In the city of Corfu, the ruins of the ancient city of Korkyra, also known as Palaiopolis, include ancient temples which were excavated at the location of the palace of Mon Repos, which was built on the ruins of the Palaiopolis. The temples are: Kardaki Temple, Temple of Artemis, and the Temple of Hera. Hera's temple is situated at the western limits of Mon Repos, close to Kardaki Temple and to the northwest.[105] It is approximately 700 m. to the southeast of the Temple of Artemis in Corfu.[105] Hera's Temple was built at the top of Analipsis Hill, and, because of its prominent location, it was highly visible to ships passing close to the waterfront of ancient Korkyra.[105]

Kardaki Temple

[edit]

Kardaki Temple is an Archaic Doric temple in Corfu, Greece, built around 500 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra (or Corcyra), in what is known today as the location Kardaki in the hill of Analipsi in Corfu.[106] The temple features several architectural peculiarities that point to a Doric origin.[106][107] The temple at Kardaki is unusual because it has no frieze, following perhaps architectural tendencies of Sicilian temples.[108]

It is considered to be the only Greek temple of Doric architecture that does not have a frieze.[106] The spacing of the temple columns has been described as "abnormally wide".[109] The temple also lacked both porch and adyton, and the lack of a triglyph and metope frieze may be indicative of Ionian influence.[110] The temple at Kardaki is considered an important and to a certain degree mysterious topic on the subject of early ancient Greek architecture. Its association with the worship of Apollo or Poseidon has not been established.

Temple of Artemis

[edit]

The Temple of Artemis is an Archaic Greek temple in Corfu, built in around 580 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra (or Corcyra), in what is known today as the suburb of Garitsa. The temple was dedicated to Artemis. It is known as the first Doric temple exclusively built with stone.[111] It is also considered the first building to have incorporated all of the elements of the Doric architectural style.[112] Very few Greek temple reliefs from the Archaic period have survived, and the large fragments of the group from the pediment are the earliest significant survivals.

The temple was a peripteral–styled building with a pseudodipteral configuration. Its perimeter was rectangular, with width of 23.46 m (77.0 ft) and length 49 m (161 ft) with an eastward orientation so that light could enter the interior of the temple at sunrise.[111] It was one of the largest temples of its time.[113]

The metope of the temple was probably decorated, since remnants of reliefs featuring Achilles and Memnon were found in the ancient ruins.[111] The temple has been described as a milestone of Ancient Greek architecture and one of 150 masterpieces of Western architecture.[112] The Corfu temple architecture may have influenced the design of an archaic sanctuary structure found at St. Omobono in Italy, near Tiber in Ancient Rome, at the time of the Etruscans, which incorporates similar design elements.[114] If still in use by the 4th-century, the temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire, when the Christian Emperors issued edicts prohibiting non-Christian worship. Kaiser Wilhelm II, while vacationing at his summer palace of Achilleion in Corfu and while Europe was preparing for war, was involved in excavations at the site of the ancient temple.

Temple of Hera

[edit]

The Temple of Hera or Heraion is an archaic temple in Corfu, built around 610 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra (or Corcyra), in what is known today as Palaiopolis, and lies within the ground of the Mon Repos estate.[115][116][105] The sanctuary of Hera at Mon Repos is considered a major temple, and one of the earliest examples of archaic Greek architecture.[105]

Large terracotta figures such as lions, gorgoneions, and Daidala maidens, created and painted in vivid colour by artisans, who were inspired by myth traditions across the Mediterranean, decorated the roof of the temple, making it one of the most intricately adorned temples of Archaic Greece and the most ambitious roof construction project of its time.[105] Built at the top of Analipsis Hill, Hera's sanctuary was highly visible to ships approaching the waterfront of the ancient city of Korkyra.[105]

The Digital Archaic Heraion Project at Mon Repos is a project that has undertaken the task of digitising the architectural fragments found at the Corfu Heraion with the aim to reconstruct in 3D the Temple at Palaiopolis in virtual space.[117]

Tomb of Menecrates

[edit]

The Tomb of Menecrates or Monument of Menecrates is an Archaic cenotaph in Corfu, built around 600 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra (or Corcyra).[118][119] The tomb and the funerary sculpture of a lion were discovered in 1843 during demolition works by the British Army who were demolishing a Venetian fortress in the location of Garitsa hill in Corfu.[120] The tomb is dated to the 6th century BC.[120]

The lion is dated at the end of the 7th century BC and it is one of the earliest funerary lions ever found.[120] The tomb and the lion were found in an area which was part of the necropolis of ancient Korkyra, which was discovered by the British army at the time.[120] According to an Ancient Greek inscription found on the grave, the tomb was a monument built by the ancient Korkyreans in honour of their proxenos (ambassador) Menecrates, son of Tlasios, from Oeiantheia. Menecrates was the ambassador of ancient Korkyra to Oeiantheia, modern day Galaxidi or Ozolian Locris,[121][122] and he was lost at sea. In the inscription it is also mentioned that the brother of Menecrates, Praximenes, had arrived from Oeiantheia to assist the people of Korkyra in building the monument to his brother.[123][118]

Other archaeological sites

[edit]In Cassiope, the only other city of ancient importance, its name is still preserved by the village of Kassiopi, and there are some rude remains of building on the site; but the temple of Zeus Cassius for which it was celebrated has totally disappeared.

Castles

[edit]The castles of Corfu, located at strategic points on the island helped defend the island from many invaders and they were instrumental in repulsing repeated Turkish invasions, making Corfu one of the few places in Greece never to be conquered by the Ottomans.

Palaio Frourio

[edit]

The old citadel (in Greek Palaio Frourio (Παλαιό Φρούριο) is an old Venetian fortress built on an artificial islet with fortifications surrounding its entire perimeter, although some sections, particularly on the east side, are slowly being eroded and falling into the sea. Nonetheless, the interior has been restored and is in use for cultural events, such as concerts (συναυλίες) and Sound and Light Productions (Ηχος και Φως), when historical events are recreated using sound and light special effects. These events take place amidst the ancient fortifications, with the Ionian Sea in the background. The central high point of the citadel rises like a giant natural obelisk complete with a military observation post at the top, with a giant cross at its apex; at the foot of the observatory lies St. George's church, in a classical style punctuated by six Doric columns,[124] as opposed to the Byzantine architectural style of the greater part of Greek Orthodox churches.

Neo Frourio

[edit]

The new citadel or Neo Frourio (Νέο Φρούριο, "New Fortress") is a huge complex of fortifications built by the British during their rule of the island (1815–63)[125] dominating the northeastern part of the city. The huge walls of the fortress loom over the landscape as one travels from Neo Limani (Νέο Λιμάνι, "New Port") to the city, taking the road that passes through the fishmarket (ψαραγορά). The new citadel was until recently a restricted area due to the presence of a naval garrison, but old restrictions have been lifted and it is now open to the public, with tours possible through the maze of medieval corridors and fortifications. The winged Lion of St Mark, the symbol of Venice, can be seen at regular intervals adorning the fortifications.

Angelokastro

[edit]

Angelokastro (Greek: Αγγελόκαστρο (Castle of Angelos or Castle of the Angel); Venetian: Castel Sant'Angelo) is a Byzantine castle on the island of Corfu,[126][127] Greece. It is located at the top of the highest peak of the island's shoreline in the northwest coast near Palaiokastritsa and built on particularly precipitous and rocky terrain. It stands 1,000 ft (305 m) on a steep cliff above the sea and surveys the City of Corfu and the mountains of mainland Greece to the southeast and a wide area of Corfu toward the northeast and northwest.[126][128]

Angelokastro is one of the most important fortified complexes of Corfu. It was an acropolis which surveyed the region all the way to the southern Adriatic and presented a formidable strategic vantage point to the occupant of the castle.

Angelokastro formed a defensive triangle with the castles of Gardiki and Kassiopi, which covered Corfu's defences to the south, northwest and northeast. The castle never fell, despite frequent sieges and attempts at conquering it through the centuries, and played a decisive role in defending the island against pirate incursions and during three sieges of Corfu by the Ottomans, significantly contributing to their defeat. During invasions it helped shelter the local peasant population. The villagers also fought against the invaders playing an active role in the defence of the castle. Angelokastro, located at the western frontier of the Empire, was instrumental in repulsing the Ottomans during the first great siege of Corfu in 1537, in the siege of 1571 and the second great siege of Corfu in 1716 causing the Ottomans to fail at penetrating the defences of Corfu in the North. Consequently the Turks were never able to create a beachhead and to occupy the island.[129]

Gardiki Castle

[edit]

Gardiki Castle (Greek: Κάστρο Γαρδικίου) is a 13th-century Byzantine castle on the southwestern coast of Corfu and the only surviving medieval fortress on the southern part of the island.[130] It was built by a ruler of the Despotate of Epirus,[131] and was one of three castles which defended the island before the Venetian era (1401–1797).

The location of Gardiki at the narrow southwest flank of Corfu provided protection to the fields and the southern lowlands of Corfu and in combination with Kassiopi Castle on the northeastern coast of the island and Byzantine Angelokastro protecting the northwestern shore of Corfu, formed a triangular line of defence which protected Corfu during the pre-Venetian era.[131][132][133]

Kassiopi Castle

[edit]

Kassiopi Castle (Greek: Κάστρο Κασσιώπης) is a castle on the northeastern coast of Corfu overseeing the fishing village of Kassiopi.[134] It was one of three Byzantine-period castles that defended the island before the Venetian era (1386–1797). The castles formed a defensive triangle, with Gardiki guarding the island's south, Kassiopi the northeast and Angelokastro the northwest.[132][133]

Its position at the northeastern coast of Corfu overseeing the Corfu Channel that separates the island from the mainland gave the castle an important vantage point and an elevated strategic significance.[134]

Kassiopi Castle is considered one of the most imposing architectural remains in the Ionian Islands,[135] along with Angelokastro, Gardiki Castle and the two Venetian Fortresses of Corfu City, the Citadel and the New Fort.[135]

Since the castle was abandoned for a long time, its structure is in a state of ruin. The eastern side of the fort has disappeared and only a few traces of it remain. There are indications that castle stones have been used as building material for houses in the area. Access to the fortress is mainly from the southeast through a narrow walkway which includes passage from homes and backyards, since the castle is at the centre of the densely built area of the small village of Kassiopi.[136][137]

Municipalities

[edit]The three present municipalities of Corfu and Diapontia Islands were formed in the 2019 local government reform from the former municipality Corfu.[3][138]

Education

[edit]Ionian Academy

[edit]

The Ionian Academy was an institution that maintained the tradition of Greek education while the rest of Greece was still under Ottoman rule. The academy was established by the French during their administration of the island as the département of Corcyre,[139][140] and became a university during the British administration,[140] through the actions of Frederick North, 5th Earl of Guilford in 1824.[141] It is also considered the precursor of the Ionian University. It had Philological, Law, and Medical Schools.

Ionian University

[edit]

The Ionian University was established in 1984, in recognition, by the administration of Andreas Papandreou, of Corfu's contribution to Education in Greece, as the seat of the first Greek university in modern times,[142] the Ionian Academy. The university opened its doors to students in 1985 and today comprises three Schools and six Departments offering undergraduate and post-graduate degree programmes and summer schools.[143][144]

Student activism

[edit]In the modern era, beginning with its massive student protests during World War II against fascist occupation, and continuing in the fight against the dictatorship of Georgios Papadopoulos (1967–1974), students in Corfu have played a vanguard role in protesting for freedom and democracy in Greece, against both internal and external oppression. For Corfiotes a recent example of such heroism is that of geology student Kostas Georgakis, who set himself ablaze in Genoa, Italy on 19 September 1970, in a protest against the Greek military junta of 1967-1974.

Culture

[edit]Corfu has a long musical, theatrical, and operatic tradition. The operas performed in Corfu were at par with their European counterparts. The phrase "applaudito in Corfu" (applauded in Corfu) was a measure of high accolade for an opera performed on the island. The Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù was the first theatre and opera house of modern Greece and the place where the first Greek opera, Spyridon Xyndas' The Parliamentary Candidate (based on an exclusively Greek libretto) was performed.

Museums and libraries

[edit]

The most notable of Corfu's museums and libraries are located in the city; these include:[145]

- The Archaeological Museum, inaugurated in 1967, was constructed to house the exhibit of the huge Gorgon pediment of the Artemis temple in the ancient city of Korkyra, excavated at Palaiopolis in the early 20th century. The pediment has been described by The New York Times as the "finest example of archaic temple sculpture extant".[146] Kaiser Wilhelm II had developed a "lifelong obsession" with the Gorgon sculpture, dating from seminars on Greek Archaeology the Kaiser attended while at the University of Bonn. The seminars were given by archaeologist Reinhard Kekulé von Stradonitz, who later became the Kaiser's advisor.[97] In 1994, two more halls were added to the museum, where new discoveries from the excavations of the ancient city and the Garitsa cemetery are exhibited.

- The Museum of Asian art of Corfu is located at the Palace of St. Michael and St. George (mainly Chinese and Japanese Arts); its unique collection is housed in 15 rooms, taking in over 12,000 artifacts, including a Greco-Buddhist art collection that shows the influence of Alexander the Great on Buddhist culture as far as Pakistan (see Greco-Buddhism).

- The Banknote Museum, located in Aghios Spyridon square, features a complete collection of Greek banknotes from independence to the adoption of the euro in 2002.

- The Byzantine Museum of Antivouniotissa, a church converted into a museum featuring rare Byzantine art.

- Kapodistrias Museum. Ioannis Kapodistrias' summer home in Koukourisa in his birthplace of Corfu has been converted to a museum commemorating his life and accomplishments and has been named in his honour.[147] Donated by Maria Desylla Kapodistria, grand niece of Ioannis Kapodistrias, former mayor of Corfu and first female mayor of Greece.

- The Music Museum of the Philharmonic Society of Corfu is located in the building of the Philharmonic Society and features scores, instruments, paintings and documents related to the music history of Corfu and the 19th-century Ionian Islands.

- The Public Library of Corfu is located at the old English Barracks, in Palaio Frourio.

- The Reading Society of Corfu has an extensive library of old Corfu manuscripts and rare books.

- The Serbian Museum of Corfu (Serbian: Српска кућа, Serbian House) houses rare exhibits about the Serbian soldiers' tragic fate during the First World War. The remnants of the Serbian Army of about 150,000 soldiers together with their government in exile, found refuge and shelter in Corfu, following the collapse of the Serbian Front as a result of the Austro-Hungarian attack of 6 October 1915. Exhibits include photographs from the three years stay of the Serbians in Corfu, together with other exhibits such as uniforms, arms and ammunition of the Serbian army, Serbian regimental flags, religious artifacts, surgical tools and other decorations of the Kingdom of Serbia.

- Solomos Museum and the Corfiot Studies Society.

Patron Saint Spyridon

[edit]

Saint Spyridon the Thaumaturgist (Miracle-worker, Θαυματουργός) is the patron saint (πολιούχος) of the city and the island. St. Spyridon is revered for the miracle of expelling the plague (πανώλη) from the island, among many other miracles attributed to him. It is believed by the faithful that on its way from the island the plague scratched one of the fortification stones of the old citadel to indicate its fury at being expelled; to St. Spyridon is also attributed the role of saving the island at the second great siege of Corfu in 1716.[148][149] The legend says that the sight of St. Spyridon approaching Ottoman forces bearing a flaming torch in one hand and a cross in the other caused panic.[70][150][151] The legend also states that the Saint caused a tempest which was partly responsible for repulsing the Ottomans.[152] This victory over the Ottomans, therefore, was attributed not only to the leadership of Count Schulenburg who commanded the stubborn defence of the island against Ottoman forces, but also to the miraculous intervention of St. Spyridon. Venice honoured von der Schulenburg and the Corfiots for successfully defending the island. Recognizing St. Spyridon's role in the defence of the island Venice legislated the establishment of the litany (λιτανεία) of St Spyridon on 11 August as a commemoration of the miraculous event, inaugurating a tradition that continues to this day.[70] In 1716 Antonio Vivaldi, on commission by the republic of Venice, composed the oratorio Juditha triumphans to commemorate this great event. Juditha triumphans was first performed in November 1716 in Venice by the orchestra and choir of the Ospedale della Pietà and is described as Vivaldi's first great oratorio.[153] Hence Spyridon is a popular first name for Greek males born on the island and/or to islanders.

Music

[edit]Musical history

[edit]

While much of present-day Greece was under Ottoman rule, the Ionian Islands enjoyed a Golden Age in music and opera. Corfu was the capital city of a Venetian protectorate and it benefited from a unique musical and theatrical heritage. Then in the 19th century, as a British Protectorate, Corfu developed a musical heritage of its own and which constitutes the nucleus of modern Greek musical history. Until the early 18th century, musical life took place in city and village squares, with performances of straight or musical comedies – known as Momaries or Bobaries. From 1720, Corfu became the possessor of the first theatre in post-1452 Greece. It was the Teatro San Giacomo (now the City Hall) named after the nearby Roman Catholic cathedral (completed in 1691).[154]

The island was also the center of the Ionian School of music, the musical production of a group of Heptanesian composers, whose heyday was from the early 19th century till approximately the 1950s. It was the first school of classical music in Greece and it was a heavy influence for the later Greek music scene, after the independence.

The three Philharmonics

[edit]

Corfu's Philharmonic Societies provide free instruction in music, and continue to attract young recruits. There are nineteen such marching wind bands throughout the island.

Corfu city is home to the three most prestigious bands – in order of seniority:

- the Philharmonic Society of Corfu use dark blue uniforms with dark red accents, and blue and red helmet plumes. It is usually called the Old Philharmonic or simply the Paliá ("Old"). Founded 12 September 1840.

- the Mantzaros Philharmonic Society use blue uniforms with blue and white helmet plumes. It is commonly called the Néa ("New"). Founded 25 October 1890.

- the Capodistria Philharmonic Union use bright red and black uniforms and plumes. It is commonly called the Cónte Capodístria or simply the Cónte ("Count"). It is the juniormost of the three (founded 18 April 1980).

All three maintain two major bands each, the main marching bands that can field up to 200 musicians on grand occasions, and the 60-strong student bandinas meant for lighter fare and on-the-job training.

The bands give regular summer weekend promenade concerts at the Spianada Green "pálko", and have a prominent part in the yearly Holy Week ceremonies.

Ionian University music department

[edit]

Since the early 1990s a music department has been established at the Ionian University. Aside from its academic activities, concerts in Corfu and abroad, and musicological research in the field of Neo-Hellenic Music, the Department organizes an international music academy every summer, which gathers together both international students and professors specialising in brass, strings, singing, jazz and musicology.

Theatres and operatic tradition

[edit]Teatro di San Giacomo

[edit]

Under Venetian rule, the Corfiotes developed a fervent appreciation of Italian opera, which was the real source of the extraordinary (given conditions in the mainland of Greece) musical development of the island during this era.[155] The opera house of Corfu during the 18th and 19th centuries was the Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo, named after the neighbouring Catholic cathedral; it was later converted into the City Hall.[155] It was both the first theatre and first opera house of Greece in modern times and the place where the first Greek opera (based on an exclusively Greek libretto), Spyridon Xyndas' The Parliamentary Candidate was performed.[155] A long series of local composers, such as Nikolaos Mantzaros, Spyridon Xyndas, Antonio Liberali, Domenico Padovani, the Zakynthian Pavlos Carrer, the Lambelet family, Spyridon Samaras, and others, all developed careers intertwined with the theatre.[155] San Giacomo's place was taken by the Municipal Theatre in 1902, which maintained the operatic tradition vividly until its destruction during German air raid in 1943.[155]

The first opera to be performed in the San Giacomo was in 1733 ("Gerone, tiranno di Siracusa"),[155] and for almost two hundred years, between 1771 and 1943, nearly every major opera from the Italian tradition, as well as many others from Greek and French composers, were performed on the stage of the San Giacomo; this tradition continues to be reflected in Corfiote operatic history, a fixture in famous opera singers' itineraries.[156]

Municipal Theatre of Corfu

[edit]

The Municipal Theatre of Corfu (Greek: Δημοτικό Θέατρο Κέρκυρας) was the main theatre and opera house in Corfu.[157] Opened in 1902, the theatre was the successor of Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù which became the Corfu city hall. It was destroyed during a Luftwaffe aerial bombardment in 1943.[157]

During its 41-year history, it was one of the premier theatres and opera houses in Greece, and as the first theatre in Southeastern Europe,[157] it contributed to the arts and to the history of the Balkans and of Europe.[158][157][159] The archives of the theatre, including the historical San Giacomo archives, all valuables and art were destroyed in the Luftwaffe bombing with the sole exception of the stage curtain, which was not in the premises the night of the bombing and thus escaped harm; among the losses are believed to have been numerous manuscripts of the work of Spyridon Xyndas, composer of the first opera in Greek.[157]

Festivities

[edit]Easter

[edit]On Good Friday, from the early afternoon onward, the bands of the three Philharmonic Societies, separated into squads, accompany the Epitaph processions of the city churches. Late in the afternoon, the squads come together to form one band in order to accompany the Epitaph procession of the cathedral, while the funeral marches that the bands play differ depending on the band; the Old Philharmonic play Albinoni's Adagio, the Mantzaros play Verdi's Marcia Funebre from Don Carlo, and the Capodistria play Chopin's Funeral March and Mariani's Sventura.[160]

On Holy Saturday morning, the three city bands again take part in the Epitaph processions of St. Spyridon Cathedral in procession with the Saint's relics.[160] At this point the bands play different funeral marches, with the Mantzaros playing Miccheli's Calde Lacrime, the Palia playing Marcia Funebre from Faccio's Amleto, and the Capodistria playing the Funeral March from Beethoven's Eroica. This custom dates from the 19th century, when colonial administrators banned the participation of the British garrison band in the traditional Holy Friday funeral cortege. The defiant Corfiotes held the litany the following morning, and paraded the relics of St. Spyridon too, so that the administrators would not dare intervene.

The litany is followed , at exactly 11:00 AM, the celebration of the "Early Resurrection"; balconies in the old city are decked in bright red cloth, and Corfiotes throw down large clay pots (the bótides, μπότηδες) full of water to smash on the street pavement, especially in wider areas of Liston and in an organised fashion.[160] This is enacted in anticipation of the Resurrection of Jesus, which is to be celebrated that same night,[160] and to commemorate King David's phrase: "Thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter's vessel" (Psalm 2:9).

Once the bótides commotion is over, the three bands parade the clay-strewn streets playing the famous "Graikoí" festive march.[161] The march, which functions as the anthem of the island, was composed during the period of Venetian rule, and its lyrics include: "Greeks, never fear, we are all enslaved: you to the Turks, we to the Venetians, but one day we shall all be free".[citation needed]

Ta Karnavalia