The First Great Train Robbery

| The First Great Train Robbery | |

|---|---|

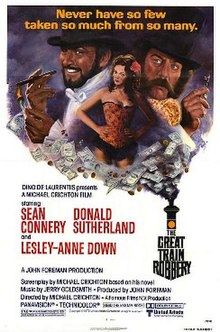

American theatrical release poster by Roger Kastel | |

| Directed by | Michael Crichton |

| Screenplay by | Michael Crichton |

| Based on | The Great Train Robbery 1975 novel by Michael Crichton |

| Produced by | John Foreman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | David Bretherton |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | Starling Films |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million[1] |

| Box office | $13 million (US/Canada)[2] |

The First Great Train Robbery (known in the United States as The Great Train Robbery) is a 1978 British heist comedy film directed by Michael Crichton, who also wrote the screenplay based on his 1975 novel The Great Train Robbery. The film stars Sean Connery, Donald Sutherland and Lesley-Anne Down.

The story is based on an actual event, the Great Gold Robbery which took place on 15 May 1855 when 3 boxes of gold bullion and coins were stolen from the guard's van of the train service between London Bridge Station and Folkestone while it was being shipped to Paris.[3]

Plot

[edit]In 1855[4] Edward Pierce, a member of London's high society, is secretly a master thief. He plans to steal a monthly shipment of gold from the London to Folkestone train which is meant as payment for British troops fighting in the Crimean War. The gold is guarded in two heavy safes in the baggage car, each of which has two locks, requiring a total of four keys. Pierce recruits pickpocket and screwsman Robert Agar. Pierce's mistress Miriam and his chauffeur Barlow join the plot, and a train guard, Burgess, is bribed into participation. The executives of the bank who arrange the gold transport, the manager Mr. Henry Fowler and the president Mr. Edgar Trent, each possess a key; the other two are locked in a cabinet at the offices of the South Eastern Railway at the London Bridge railway station. To hide the robbers' intentions, wax impressions are to be made of each of the keys.

Pierce ingratiates himself with Trent by feigning a shared interest in ratting. He also begins courting Trent's daughter, Elizabeth, and learns from her the location of her father's key. Pierce and Agar break into Trent's home at night, locate the key and make a wax impression before making a getaway.

Pierce targets Fowler through his weakness for prostitutes. Miriam reluctantly poses as "Madame Lucienne", a courtesan in an exclusive bordello, meets with Fowler and asks him to undress, forcing him to remove the key worn round his neck. While Fowler is distracted by Miriam, Agar makes an impression of his key. Pierce then stages a phony police raid to rescue Miriam, forcing Fowler to flee to avoid a scandal.

The keys at the train station prove a much harder challenge. After a daytime diversionary tactic with a child pickpocket fails because Agar cannot wax them in the time available, Pierce decides to "crack the crib" at night. The operation is a matter of timing, because the officer guarding the railway office at night leaves his post only once, for seventy-five seconds, to go to the toilet. Pierce plans to use "snakesman" (cat burglar) Clean Willy to climb the station's wall, climb down into the station, enter the office via a skylight in the ceiling, and open the key cabinet from within. Because Clean Willy is incarcerated at Newgate Prison, Pierce and Agar first have to arrange for him to break out, using a public execution as a distraction. With Willy's help, the criminals succeed in making impressions of the keys without detection.

Clean Willy is subsequently arrested after being caught pick-pocketing and informs on Pierce. The police use Willy to lure Pierce into a trap, but the master cracksman eludes capture. Clean Willy escapes from his captors, but is murdered by Barlow on Pierce's orders. The authorities, now aware that a robbery is imminent, increase security by having the baggage car padlocked from the outside until the train arrives at its destination and forbidding anyone but the guard to travel in the baggage van. Any container large enough to hold a man must be opened and inspected before it is loaded on the train.

Pierce smuggles Agar into the baggage car disguised as a corpse in a coffin. Pierce plans to reach the car across the coach roofs while the train is under way, but he and Miriam encounter Fowler, who is riding the train to Folkestone to accompany the shipment. After arranging for Miriam to travel in the same compartment as Fowler to divert his attention, Pierce travels down the roof of the train and unlocks the baggage van's door from the outside. He and Agar replace the gold with lead bars and toss the bags of gold off the train at a prearranged point. However, soot from the engine's smoke has stained Pierce's skin and clothes, and he is forced to borrow Agar's suit, which is much too small for him. The jacket splits across the back when he disembarks at Folkestone. The police become suspicious and arrest him before he can rejoin his accomplices.

Pierce is put on trial for the robbery. While exiting the courthouse, he receives the adulation of the crowds, who consider him a folk hero for his daring act. In the commotion, a disguised Miriam kisses him, slipping a key to his handcuffs from her mouth to his. Agar is also present, disguised as a police van driver. Before he can be put into the wagon, Pierce frees himself and escapes with Agar, to the jubilation of the crowd and the chagrin of the police.

Cast

[edit]- Sean Connery as Edward Pierce / John Simms

- Donald Sutherland as Agar

- Lesley-Anne Down as Miriam

- Alan Webb as Edgar Trent

- Malcolm Terris as Henry Fowler

- Robert Lang as Sharp

- Michael Elphick as Burgess

- Wayne Sleep as William "Clean Willy" Williams

- Pamela Salem as Emily Trent

- Gabrielle Lloyd as Elizabeth Trent

- George Downing as Barlow

- James Cossins as Harranby

- André Morell as Judge

- Peter Benson as Station Master

- Janine Duvitski as Maggie

- Peter Butterworth as Putnam

- Brian Glover as Captain Jimmy

- Geoffrey Ferris as Pickpocket

Production

[edit]Film rights to the novel were bought in 1975 by Dino de Laurentiis.[5] In 1977 it was announced the film would be made in Ireland by American International Pictures with Sean Connery and Jacqueline Bisset.[6]

Crichton deliberately varied the film from his book. He said "the book was straight, factual but the movie is going to be close to farce."[1]

Sean Connery originally turned down the film after reading the script, judging it "too heavy." He was asked to reconsider and read the original novel. After meeting Crichton, Connery changed his mind.[7]

Sean Connery performed most of his own stunts in the film, including the extended sequence on top of the moving train.[8] The train was composed of J-15 class 0-6-0 No 184 of 1880, with its wheels and side rods covered and roof removed, leaving only spectacle plate for protection to give it a look more akin to the 1850s, and coaches that were made for the film from modern railway flat wagons. Connery was told that the train would travel at only 20 miles per hour during his time on top of the cars. However, the train crew used an inaccurate means of judging the train's speed. The train was actually doing speeds of 40 to 50 miles per hour. Connery wore soft rubber soled shoes and the roofs of the carriages were covered with a sandy, gritty surface. Connery actually slipped and nearly fell off the train during one jump between two carriages, and had difficulty keeping his eyes free of smoke and cinders from the locomotive.[9]

Heuston Station in Dublin stood in for 'London Bridge Station' in the film.[10] During the filming at the station, a diesel locomotive leaked a large quantity of fuel onto the tracks by the platform. When the production company's steam engine rolled onto the same tracks, embers dropping from the underside of the locomotive ignited the fuel soaked track, momentarily producing a very large fire within the station.[11]

Origins of the plot

[edit]The film's plot is loosely based on the Great Gold Robbery of 1855, in which a cracksman named William Pierce engineered the theft of a trainload of gold being shipped to the British Army during the Crimean War.[1] The gold shipment of £12,000 (equal to £1,416,472 today) in gold coin and ingots from the London-to-Folkestone passenger train was stolen by Pierce and his accomplices, a clerk in the railway offices named Tester, and a skilled screwsman named Agar. The robbery was a year in the planning and involved making sets of duplicate keys from wax impressions for the locks on the safes, and bribing the train's guard, a man called Burgess.[12]: 210 Crichton, the author of the book and the screenplay, was inspired by Kellow Chesney's 1970 book The Victorian Underworld, which is a comprehensive examination of the more sordid aspects of Victorian society.

In his screenplay Crichton based his character "Clean Willy" Williams on another real-life character from Chesney's book, a housebreaker named Williams (or Whitehead) who, sentenced to death in Newgate Prison, escaped from prison by climbing the 15-metre (50-ft.) tall sheer granite walls, squeezing through the revolving iron spikes at the top, and climbing over the inward projecting sharp spikes above them before making his escape over the roofs.[12]: 187 The only completely fictional character in the film is Miriam (Lesley-Anne Down).

The film also draws loose parallels to the 1903 film of the same name. The 1903 film has just 18 shots, but the film borrows two scenes, one in which Pierce (the 1903 characters are unnamed) is on top of the train, and another when a person is thrown off the moving train.

Filming locations

[edit]Although set in London and Kent, most of the filming took place in Ireland. In particular, the final scenes were filmed in Trinity College, Dublin[13] and Kent railway station in Cork. Heuston Station in Dublin stood in for London Bridge railway station. The scenes on the moving train were filmed on the Mullingar to Athlone railway line (now closed) at Castletown Geoghegan Station. The train driver was John Byrne from Mullingar, now deceased. Moate railway station is the location for Ashford station.

The two locomotives featured were both J-15 0-6-0s, No 184 of 1880, and No 186 of 1879.[14][15]

Music

[edit]The film's soundtrack was written by Oscar-winning composer Jerry Goldsmith. The score was his third collaboration with writer/director Michael Crichton following Pursuit (1972) and Coma (1978). The music for two pianos played by the characters Elizabeth (Gabrielle Lloyd) and Emily Trent (Pamela Salem) is from the third movement of Mozart's Sonata for Two Pianos in D major, K. 448 Molto Allegro.

Release

[edit]The film opened 21 December 1978 at the Leicester Square Theatre in London.[16] It was rumoured that a charity preview was to be held on 18 December 1978 in aid of a trust fund for the wife and children of cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth who died before the film was released and to whom the film was dedicated.[17]

Reception

[edit]The Great Train Robbery has a critical rating of 77% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 30 reviews.[18] The site's critics praised the film's comedic tone, action sequences, and Victorian details. Variety wrote that "Crichton's film drags in dialog bouts, but triumphs when action takes over."[19] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four and singled out Connery, writing that the actor "is one of the best light comedians in the movies, and has been ever since those long-ago days when he was James Bond."[20] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised director Crichton's "amplitude...in this visually dazzling period piece,"[21] and that "the climactic heist of the gold, with Mr. Connery climbing atop the moving railroad cars, ducking under bridges just before a possible decapitation, is marvelous action footage that manages to be very funny as it takes your breath away."[21] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote that it "takes too much time to get to the robbery itself." He found very little suspense in the first half of the movie "because we know that Connery's gang must get the keys or we won't be able to see the big robbery of the film's title."[22] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "an intelligent and handsome work. It is just a little slow, dull and bloodless—pure Victorian, when a dash or two of Elizabethan vivacity couldn't have hurt."[23] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote that "While the movie boasts an undeniably exciting highlight, it lacks an undercurrent of excitement ... It's beginning to look as if Crichton's filmmaking carburetor is tuned a bit low. Perhaps his approach is too dry and cautious to produce an explosive, uninhibited mixture of thrills and humor."[24]

Accolades

[edit]- Edgar Award, Best Motion Picture Screenplay, 1980 — Michael Crichton

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Owen, Michael (28 January 1979). "Director Michael Crichton Films a Favorite Novelist". New York Times. p. D17.

- ^ The Great Train Robbery at Box Office Mojo

- ^ The Great Gold Robbery Wikipage

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY". rogerebert.com/. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (21 September 1975). "Movies: Director Dino hits the shores of America". Chicago Tribune. p. e16.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Godfrey (10 June 1977). "Hollywood company to make $5m. film here". The Irish Times. p. 13.

- ^ Sterritt, David (3 April 1979). "Sean Connery: Ex-Milkman with a Famous Face". Christian Science Monitor. p. B24. ProQuest 512201486.

- ^ Mann, Roderick (19 December 1978). "The Diagnoses of Dr. Crichton". Los Angeles Times. p. f16.

- ^ Bray, Christopher (2011). Sean Connery: A Biography. New York: Pegasus. ISBN 978-1-4532-1770-2.

- ^ McCormack, Stan (13 August 2020). "When the movies came to town". Westmeath Examiner. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0079240/trivia?ref_=tt_trv_trv. Retrieved 14 March 2017. [user-generated source]

- ^ a b Chesney, Kellow (1970). The Victorian Underworld. London: Maurice Temple Smith Ltd. ISBN 0-85117-002-1.

- ^ David Ingoldsby. "The Great Train Robbery (1978)". Shot at Trinity. Trinity College Dublin. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ 31interactive.co.uk. "No. 184". www.steamtrainsireland.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ 31interactive.co.uk. "No. 186". www.steamtrainsireland.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ French, Philip (17 December 1978). "Keys of scag". The Observer. p. 18.

- ^ Peterborough (14 December 1978). "London Day by Day". The Daily Telegraph. p. 18.

- ^ "The Great Train Robbery (1979)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ "Review: 'The First Great Train Robbery'". Variety. 17 January 1979. p. 21.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (9 February 1979). "The Great Train Robbery". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (2 February 1979). "The First Great Train Robbery (1979)". New York Times.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (12 February 1979). "'Train Robbery' action languishes in preliminaries". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 2.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (2 February 1979). "A Stickup in Slo Mo". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (9 February 1979). "The Great Train Robbery". The Washington Post. C12.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

External links

[edit]- 1978 films

- 1970s British films

- 1970s crime thriller films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s heist films

- 1970s historical films

- British crime thriller films

- Films shot in Dublin (city)

- British heist films

- British historical films

- Crime films based on actual events

- Edgar Award–winning works

- Films about train robbery

- Films based on crime novels

- Films based on works by Michael Crichton

- Films directed by Michael Crichton

- Films produced by John Foreman (producer)

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films set in 1855

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in the Republic of Ireland

- Films with screenplays by Michael Crichton

- Rail transport films

- United Artists films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language historical films