Maurice Yaméogo

Maurice Yaméogo | |

|---|---|

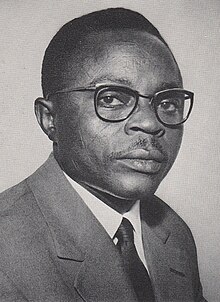

Yaméogo in 1960 | |

| 1st President of Upper Volta | |

| In office 5 August 1960 – 3 January 1966 | |

| Preceded by | None (position first established) |

| Succeeded by | Sangoulé Lamizana |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 December 1921 Koudougou, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) |

| Died | 15 September 1993 (aged 71) Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso |

| Nationality | Upper Voltian |

| Political party | Union Démocratique Voltaïque |

| Spouse(s) | Felicité Zagré (d. 1998) Suzanne de Monaco Jeanette |

| Signature |  |

Maurice Nawalagmba Yaméogo (31 December 1921 – 15 September 1993) was the first President of the Republic of Upper Volta, now called Burkina Faso, from 1960 until 1966.

"Monsieur Maurice" embodied the Voltaic state at the moment of independence. However, his political ascension did not occur without difficulties. As a member of the colonial administration from 1946, Maurice Yaméogo found a place for himself in the busy political landscape of Upper Volta thanks to his skill as a speaker. In May 1957, during the formation of the first Upper Voltaic government instituted under the Loi Cadre Defferre, he joined the coalition government formed by Ouezzin Coulibaly, as minister for agriculture and a member of the Voltaic Democratic Movement (MDV). In January 1958, threatened by a vote of censure, Coulibaly enticed Maurice Yaméogo and his allies in the assembly to join the Voltaic Democratic Union-African Democratic Assembly (UDV-RDA) in exchange for promises of promotion within the government. Maurice Yaméogo rose to be his second in command, with the portfolio of the Interior, a position which allowed him to assume the role of interim head of government, following Coulibay's death in September 1958.

His rather shaky political ascendancy was reinforced by circumstances. After the proclamation of the Republic of Upper Volta on 11 December 1958, he made a surprising volte-face with respect to the Mali Federation advocated by Léopold Sédar Senghor. The Voltaic assembly supported Upper Volta's membership in the Federation, but Yaméogo opted for political sovereignty and limited economic integration with the Conseil de l'Entente. Then, by means of controversial manoeuvres, Yaméogo eliminated all parliamentary opposition. The UDV-RDA was purged of his enemies and he imposed a one party system. Upper Volta found itself under a dictatorship even before its independence on 5 August 1960.

In foreign policy, Yaméogo envied and admired the international success of his colleague Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the President of Côte d'Ivoire, who defied the anti-communists by establishing an ephemeral customs union (1961–1962) with the "progressivist" Ghana of Kwame Nkrumah. Houphouët-Boigny nevertheless remained his closest ally and in December 1965, Yaméogo signed an agreement with him to extend dual nationality to citizens of both countries. However, this project did not reach fruition. On 3 January 1966, as a result of severe financial austerity measures, Yaméogo's corrupt regime was overthrown by a peaceful protest organised by the unions, traditional chieftains and the clergy. In 1993, he died after having been rehabilitated by President Blaise Compaoré.

Early life

[edit]

According to his official biography, Maurice Yaméogo was born on 31 December 1921 at Koudougou, a town 98 km west of Ouagadougou, along with his twin sister Wamanegdo.[1] He was the son of Mossi peasants,[2] whom he described as a "heathen family, completely given to a whole mob of superstitions."[2] They gave him the name Naoua Laguemba[3] (also spelt Nawalagma)[2] which means "he comes to unite them.".[3]

From a very young age, Naoua Laguemba was very interested in Christianity.[4] This inclination resulted in a great deal of bullying from his family.[4] It is reported that the young Yaméogo received an emergency baptism on 28 July 1929, a year before schedule, after being struck by lightning.[5] The priest Van der Shaegue who performed the baptism gave him Maurice as a patron saint.[5] His mother died three days later, supposedly from the shock.[5] After these events, he adopted the name Maurice Yaméogo, intending to become a priest.[5]

After spending a few years at school in his village, Maurice Yaméogo was admitted to the Minor Seminary of Pabré.[6] On 5 September 1934, he left his family to pursue his studies.[6] Pabré was one of the most prestigious institutions in the country; aside from the fact that it produced most of the country's priests, the Minor Seminary's students also filled the very highest ranks of public and private administration.[7] As a result, he met many of the rising stars of Upper Volta, such as Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Joseph Ouédraogo, and Pierre Tapsoba, with whom he formed a close friendship.[8] But his relationships strayed far from the ecclesiastical standard.[8] Yaméogo wanted to be a priest, but he was very keen on women and parties.[3][8] In 1939, he left the Minor Seminary of Pabré, without graduating.[9][10]

Professional career

[edit]Despite failing to graduate, Yaméogo's education allowed him to gain a public role as a shipping clerk for the French Colonial Administration.[11] This extremely prestigious post meant success, security and prestige.[11] In this period he increased his involvement with women. He became enamoured of a mixed-race woman, Thérèse Larbat, whose father refused to allow him to marry her because he was an African and was not "civilised enough" to maintain her well-being.[12] Yaméogo was offended by this, but eventually, he resigned himself to marrying an educated woman from Koudougou, Félicité Zagré.[13] Together they presented themselves as the "evolved" couple of Koudougou; Félicité was the only African in the town who dressed like a European.[13]

In 1940,[14] as part of the World War II war effort, Yaméogo was sent to Abidjan in lower Côte d'Ivoire, a paradise for "evolved" Africans.[15] Regular parties were held there in which Yaméogo sought to increase his social standing.[15] He sought among other things to make many friends among the "evolved" non-Voltaic people.[16] In Abidjan Yaméogo was shocked by the fact that some Voltaic businessmen were illegally trafficking workers in order to supply huge plantations with workers. In Upper Volta, Maurice also worked as a clerk for the Administrative, Accounting and Finance Services (SAFC) of the French Colonial Administration. For this purpose, he was appointed in towns like Dedougou and Koudougou. Yaméogo was later appointed the head of the CFTC syndicate (French Confederation of Christian Workers) of his corporation, and vice-president of CFTC Upper-Volta.

Early political career

[edit]On his return to his native town after the war, he was elected to the first territorial assembly of Côte d'Ivoire as the general councillor for Koudougou on 15 December 1946.[17] Upper Volta had ceased to exist after 1932, being divided up between Côte d'Ivoire, French Sudan and Niger. This did not please the people of Upper Volta, who elected Philippe Zinda Kaboré to the French National Assembly in November 1946 with a mandate to restore Upper Volta.[18] Yaméogo joined Kaboré's entourage in the hope of thereby accelerating his own rise.[19] When Kaboré died on 24 May 1947, Yaméogo positioned himself as his spiritual heir.[19]

On 4 September 1947, Upper Volta was restored with its 1932 borders. Subsequently, a French law of 31 March 1948 instituted the Territorial Assembly of Upper Volta.[20] This assembly contained fifty seats, thirty-four of which were to be held by the general counsellors elected while Upper Volta was partitioned.[21] Yaméogo was part of this group and planned to sit as part of Kaboré's Voltaic Democratic Party (PDV), the local branch of the African Democratic Assembly (RDA).[22] However, the PDV-RDA suffered an electoral set-back. In the partial elections between 30 May and 20 June, it secured only three of the sixteen seats up for election, losing the other thirteen to the Voltaic Union (UV).[23] Then, on 27 June 1948, the PDV-RDA suffered a defection to the UV, led by Henri Guissou.[23] Yaméogo too joined the UV, swearing that he would never again be a member of the RDA.[22]

Grand counsellor of the AOF (1948–1952)

[edit]

When the assembly finally met, the general counsellors elected senators to the Council of the Republic, the counsellors of the French Union and the Grand Counsellors who would sit on the Grand Council of French West Africa (AOF) in Dakar.[24] In the discussions, Yaméogo had been left to one side.[25] Outraged, he attempted to make his voice heard within the party, but he was judged too ambitious and his requests were not heeded.[26] Thus he decided to appeal directly to Father Goarnisson, a European who had been chosen by the college of natives for one of the grand counsellor posts.[26] The priest was persuaded by him to withdraw his candidacy and support Yaméogo.[26] Thus, on 28 July 1948,[27] Yaméogo was elected grand counsellor of French West Africa for Upper Volta.

This was a great achievement; Yaméogo was barely twenty-six years old. Portraits of him as Grand Counsellor decorated the houses of his parents and friends.[28] At Dakar, his wife Félicité enjoyed the role of mistress of the house, hosting the governor-general Paul Béchard with pomp, organising receptions for the "evolved" and Yaméogo's colleagues, who included deputy mayor Lamine Gueye, president of the Grand Council.[28]

At Dakar, Yaméogo once more slid towards the RDA.[29] At the legislative elections of 17 June 1951, the PDV-RDA presented a single list with the doctor Ali Barraud, while the UV was caught up in internal dissension.[30] Joseph Conombo organised the main party list, Union for the Defense of the Interests of Upper Volta, which received 146,861 votes out of 249,940 and thus obtained three of the four seats up for election.[31] The left wing of the UV, led by the outgoing deputy Nazi Boni,[32] also presented a list, The Economic and Social Action of the Interests of Upper Volta, which secured the fourth seat with 66,986 votes.[33] Meanwhile, the two grand counsellors, Bougouraoua Ouédraogo and Maurice Yaméogo, issued an independent list, which did not meet with any success.[30]

Setback (1952–1957)

[edit]The electoral setbacks continued in the territorial elections of 30 March 1952. Yaméogo returned to his private role as a shipping clerk on the orders of governor Albert Mouragues.[30] The governor of Upper Volta was known for his repressive policy towards the RDA, which, despite its rupture with the French Communist Party (PCF) in October 1950, was still suspected of communist sympathies.[21] The uncertain relationship between Yaméogo and the RDA was surely responsible for his reassignment to Djibo in the Sahel.[30]

Less than a year later, he returned to Ouagadougou to oversee the health service.[34] He participated in the establishment of a club of officials.[34] Then, hoping to relaunch his political career, Yaméogo re-entered the UV thanks to the support of his old school friend from Pabré, who had become president of the General Council, Joseph Ouédraogo.[34] On stage with the latter, he was named joint-secretary during the first congress of the territorial union of the French Confederation of Christian Workers (CFTC) in 1954, in spite of He.[35]

In the same year, the two wings of the UV clashed. On one side, deputy Nazi Boni founded the Popular Movement for African Development (MPEA) on 27 October 1954.[36] On the other side, the leaders of the party terminated the UV in order to create the Social Party for the Education of the African Masses (PSEMA) in December 1954.[36][37] Yaméogo once again tried t set up a separate group centred around himself, but without success. His list at the legislative elections of 2 January 1956, which included his friend Pierre Tapsoba, suffered a defeat.[38] So too did his request to the newly elected mayor of Ouagadougou, Joseph Ouédraogo, for the post of general secretary of the mayor.[39]

Minister of Upper Volta under the Loi Cadre Defferre (1957–1958)

[edit]

On 29 September 1956, PSEMA merged with the PVD-RDA to form the United Democratic Party (PDU).[40] Despite his links with both of these parties, Yaméogo joined a new party in July 1956, the Voltaic Democratic Movement (MDV), founded by Gérard Kango Ouédraogo and the French captain Michel Dorange, in which he took on the role of financial controller.[41] In the territorial elections of 30 March 1957, the MDV list led by Maurice Yaméogo at Koudougou,[42] which included his cousin Denis Yaméogo and the Haitian-Arab Nader Attié scored a surprising victory over the PDU list led by Henri Guissou, winning all six of the seats which were up for election.[39] This victory was certainly due to Yaméogo's "American style campaign," characterised by numerous meetings in the markets.[42]

As a result of the elections, 70 territorial deputies were elected.[43] The PDU held 39 of them, the MDV had 26 and the MPEA of Nazi Boni had 5.[43] These elections, which followed the entry into force of the Loi Cadre Defferre of 1956, were intended to produce a new local government. Rather than rule alone, the leader of the PDU, Ouezzin Coulibaly chose to establish a coalition government, with seven PDU ministers and five MDV ministers.[43] Maurice Yaméogo took the portfolio of agriculture in the first government, under Yvon Bourges, the last French Governor in Upper-Volta.[44]

Very quickly, tensions broke out in the PDU. During investigative meetings in September 1957, the former leader of PSEMA, Joseph Conombo, repudiated the affiliation of his party to the RDA under the control of Ouezzin Coulibaly.[45] Conombo left the coalition government with six other deputies in order to re-establish PSEMA.[45] Coulibay on the other hand transformed the PDU into the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV) and affiliated it with the RDA.[45][46] After these events, the UDV-RDA took an absolute majority in the assembly, while an anti-Ouezzin parliamentary group formed in December 1957, consisting of PSEMA, the MPEA and the MDV.[47] Thus, from being a member of government, Yaméogo found himself in the parliamentary opposition. On 17 December, Joseph Conombo submitted a motion to name a new parliamentary group, a motion of no confidence in the government, which passed.[48] Coulibaly refused to resign: the Loi Cadre Defferre explicitly state that in the case of a vote of no confidence, the government "could" resign, not that it "was removed", from office.[48] Upper Volta faced a political crisis.

In January 1958, Coulibaly resolved the situation by poaching Maurice Yaméogo,[49] who brought the MDV deputies from Koudougou with him (Nader Attié, Gabriel Traoré et Denis Yaméogo)[49] and some other counsellors like Mathias Sorgho.[50] With this new majority, the UDV-RDA established a new government on 22 January 1958.[49] In the new cabinet of 6 February, composed solely of members of UDV-RDA, Yaméogo was promoted to the second highest ranking position in the government, with the strategi position of Minister of the Interior,[10] while his cousin Denis took the portfolio of Labour and Social Affairs.[51] Ouezzin Coulibaly was taken to Paris for health reasons on 28 July 1958 and Yaméogo was placed in charge in his absence.[52] On 4 September 1958, Oezzin Coulibaly died and Maurice Yaméogo assumed the role of acting head of government.[53]

President of Upper Volta (1960–1966)

[edit]Establishment of personal power

[edit]After the people of Upper Volta had approved the constitution of the French Community on 28 September 1958, and therefore reinforced their state's autonomy, the territorial assembly met on 17 October 1958 to designate Ouezzin Coulibaly's successor.[54] On that day, Moro Naba Kougri made an unsuccessful attempt to install a constitutional monarchy.[55] Kougri, who had the support of Colonel Chevreau, the commander of the French Army in Upper Volta, gathered around 3,000 of his supporters around the assembly and attempted to influence the choice of the new president of the council.[56] Yaméogo's quick response to this demonstration certainly played in his favour during the rescheduled vote of the assembly on the 20 October, at which he was elected as president of the council.[57]

Elimination of parliamentary opposition

[edit]From April 1958, the opposition in the territorial assembly was united as the Voltaic Regroupment Movement (MRV), the local branch of the African Regroupment Party (PRA),[51] the new international African opposition to the African Democratic Rally (RDA). After Moro Naba Kougri's attempted coup, the MRV-PRA approached Yaméogo,[57] who formed a union government consisting of seven UDV-RDA ministers and five MRV-PRA ministers on 10 December 1958.[57] The next day, the Republic of Upper Volta was proclaimed and the Territorial Assembly assumed legislative and constituent powers.[57] Yaméogo retained his post as president of the council and also became Minister of Information and secretary of the youth section of the UDV-RDA.[10]

After received special powers from the assembly on 29 January 1959,[58] Yaméogo used his new prerogatives to dissolve the assembly on 28 February.[59] A new division of electoral districts had taken place.[60] A majority list ballot was adopted in the two least populated districts and a proportional representation system was adopted in the two most populated districts.[61] This manoeuvre allowed the UDV-RDA to win 64[61] (or 66)[62] seats in the legislative elections of 19 April. THE MRV-PRA won only 11 (or 9)[62] seats. Turnout was 47%.[61]

On 25 April, the new assembly confirmed Yaméogo in his position as President of the council.[60] He became minister of justice and minister for veterans on the same day.[10] On 1 May, he formed a homogenous UDV-RDA government.[60] Soon the opposition consisted of only three members, following defections in favour of the majority.[62] The internal position of the president of the council was reinforced on the 25th and 26 August, following the expulsion of the old RDA spokesman Ali Barraud and the party's secretary general Joseph Ouédraogo from the UDV-RDA.[60] This was followed by a decree on 29 August, dissolving the municipal council of Ouagadougou, which was led by Joseph Ouédraogo.[63] An administration committee led by Joseph Conombo replaced it.[63] No one seemed able to resist the man who was now nicknamed "Monsieur Maurice." Even the most intractable members of the opposition, led by Gérard Kango Ouédraogo finally rejoined the UDV-RDA in Autumn 1959, officially putting an end to the MRV.[64] There was no longer any parliamentary opposition. On 11 December 1959, Yaméogo was elected as the first President of the Republic of Upper Volta without opposition.[65] Extremely distrustful, Yaméogo entrusted power during his overseas absences to the only European on his staff, the administrator of colonies Michel Frejus.[66]

Single party system

[edit]

On 22 May 1959, Yaméogo received a new grant of special powers for six months.[66] This exceptional measure allowed him to compose a legislative arsenal against the opposition.[66] Then, on 6 October 1959, Nazi Boni established the Voltaic National Party as a local branch of the Party of the African Federation (PFA) and Yaméogo dissolved it on the grounds that the reference to the PFA was unconstitutional.[67] Two days later, Boni tried again, establishing the Republican Liberty Party (PRL).[67] This was banned on 6 January 1960, on the grounds that the flag of the Federation of Mali (which Yaméogo had broken away from) had been flown at Boni's house.[67] After protesting this decision publicly, Nazi Boni was subjected to a judicial investigation.[67] On 22 February, it was the turn of Gérard Kango Ouédraogo, member of the UDV-RDA, who attempted to create a new Party of Peasant Action (PAP).[67] Yaméogo vetoed this party with an official declaration.[68] The one-party system was entrenched.

On 12 March, the President of the Republic invited Nazi Boni and Joseph Ouédraogo to a reconciliation meeting. They declined.[68] On 28 June, an open letter criticising the government's actions was signed by both of them, as well as Diongolo Traoré, Edouard Ouédraogo et Gabriel Ouédraogo, in the hope of organising a roundtable discussion.[69] In response, Yaméogo had them arrested on 2 July and imprisoned at Gorom-Gorom, except for Nazi Boni who once more went into exile.[69] When the country became independent on 5 August 1960,[52] all forms of opposition had been silenced.[69]

The dictatorship was affirmed by the proclamation of 30 November[70] of a new constitution which conferred extended powers on Yaméogo.[71] This constitution had been adopted by the National Assembly on 6 November and approved by the people in a referendum on 27 November.[70] As dictator, Yaméogo remained easy-going. Attempting to spare his main opponents, he used diplomatic means to remove some of them, like Gérard Kango Ouédraogo, whom he appointed ambassador to Great Britain,[72] or Henri Guissou, whom he dispatched to Paris. The few political prisoners were released in exchange for a simple declaration of support for the regime.[73] Joseph Ouédraogo requested to rejoin the party in February 1962 at the second UDV-RDA party congress.[74] In the course of this congress, Yaméogo was removed as president of the party and instead appointed secretary general, a role which he held as leader of the movement.[75]

Paranoia, ministerial instability and corruption

[edit]Yaméogo became more paranoid after the 13 January 1963 coup in neighboring Togo resulted in the death of President Sylvanus Olympio. Two days after the coup, Joseph Ouédraogo was arrested again along with the union leader Pierre-Claver Tiendrébéogo, party official Ali Soré, and Ambassador to the UN Frédéric Guirm. A Security Court was established, with the accused appearing there without the right to be defended by attorneys. A police inquiry refuted the existence of a plot against Yaméogo.[76] His cousin, interior minister Denis Yaméogo, was arrested for providing him with false statements. After an imprisonment, Denis Yaméogo was reinstated to his duties in 1965.[77] The investigation, according to Guirma, proved that the informants were men of Maxime Ouédraogo,[77] Minister of Public Service and Labour.[76] In June 1963, Maxime Ouédraogo was removed from office and arrested.[76] This demonstrated one of the characteristics of Yaméogo regime: ministerial instability. Each year many hasty ministerial changes were made.[75] Depending on his moods,[78] the President of the Republic announced on the radio, without prior consultation, appointment or removal of ministers.[75]

Maxime Ouédraogo was officially imprisoned for theft and misappropriation of the funds of the Central Cooperative of Upper Volta (CCCHV).[76] Embezzlement was a common practice in the nation's government.[79] Maurice Yaméogo was well known for this. His wife Félicité spared no expense in fur coats and valuable cosmetics while her children bought sports cars.[80] Meanwhile, the president spent more than half a year abroad in sumptuous villas and thermal spas.[80] Nonetheless, the President's way of life did not improve his mood.[81] Beginning in 1964, he became obsessed about the establishment of a single union subservient to a single institutional party. Already, at the Congress of the UDV-RDA in 1962, he invited the legislators of the country to achieve unity within the National Union of workers of Upper Volta (UNST-HV).[82] Since this did not happen, the National Assembly voted on 27 April 1964 to pass a law requiring unions to join the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU), under penalty of immediate dissolution. In its charter OATUU allowed only one union per country: for Upper Volta this was the UNST-HV. All unions which refused to join the UNST-HV, were labeled "illegal" and suffered state repression.[83]

Maurice Yaméogo became the subject of a cult of personality as evidenced by stamps printed with his image. He was the sole leader of the Republic of Upper Volta and was the only candidate for the presidential election on 3 October 1965. He was "triumphantly" reelected with 99.97% of votes.[84] During the parliamentary elections of 7 November, where the participation rate was 41%, the single list of candidates he imposed won 99.89% of votes.[84] On 5 December, Yaméogo loyalists were also victorious in the municipal elections, as the UDV-RDA swept all positions.[85]

Foreign affairs

[edit]Reversal on the Mali Federation (1958–1959)

[edit]

After his election as President of the council on 20 October 1958, Maurice Yaméogo faced the question of whether or not to integrate Upper Volta into the Mali Federation. He showed some hesitation on this issue,[86] although the Voltaic political elite seemed to be generally favourable.[57] On 12 January 1959, his lack of enthusiasm changed dramatically.[87] By chance, one of the members of the Voltaic delegation to the federal assembly in Dakar for the 14th to 17 January died and Yaméogo replaced him.[87] In Dakar, very skillfully, he had himself elected vice-president of the Federal Assembly.[59]

On 28 January, in his role as head of government, he demanded that the Voltaic Assembly ratify the federal constitution.[58] Although the 59 deputies present approved this unanimously, there was fear of a new coup attempt by Moro Naba Kougri with the anti-federalist deputy Michel Dorange.[58] Taking advantage of this threat, Yaméogo successfully obtained the extension of his emergency powers.[58]

According to the then high commissioner Paul Masson, Yaméogo had changed his mind about the Federation in the course of these events and sought Masson's assistance in legally extracting Upper Volta from its engagements.[88] On his advice,[88] the Voltaic civil service and French jurists elaborated a new constitution which he had 40 hastily reconvened deputies ratify on 28 February, threatening to use his emergency powers to dissolve the Assembly if they refused.[89] Afraid that they would not be re-elected, the deputies did as they were told. At the end of the meeting, Yaméogo dissolved the Assembly anyway.[89] To justify his actions, Yaméogo organised a referendum on the constitution on 15 March, which passed with 69% of the votes.[90] Completing this volte-face, Yaméogo co-founded an organisation hostile to the Mali Federation, the Conseil de l'Entente, on 29 May 1959, with Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Côte d'Ivoire, Hamani Diori of Niger, and Hubert Maga of Dahomey.[60] The deputies elected in April acknowledged and ratified Upper Volta's membership of this organisation on 27 June.[60]

Collapse of relations with Côte d'Ivoire and France (1960-1961)

[edit]Within the Conseil de l'Entente, a quarrel about "leadership" developed between Yaméogo and Félix Houphouët-Boigny.[91] Initially the dispute was simply about the division of customs revenues, which Yaméogo considered unfair.[91] However, Yaméogo's pride rapidly became the true reason for the tensions. Yaméogo held the presidency of the Conseil de l'Entente from 1960 to 1961, but Houphouët-Boigny, who was favoured by Paris, continued to direct the Entente's discussions and negotiations on his own and to get all the kudos.[91] On 12 February 1961, Yaméogo unexpectedly announced his refusal to sign the defence agreements which Houphouët-Boigny had negotiated with France on behalf of the four members of the Entente.[91] This decision led to a deterioration of relations between Côte d'Ivoire and Upper Volta.[92] Relations between Upper Volta and France were also harmed by this and deteriorated further after Yaméogo expelled the French High Commissioner Paul Masson on false charges of conspiracy.[93][94]

For the Burkinabe historian Yacouba Zerbo, the causes of Yaméogo's refusal lie in a desire for independence,[95] combined with his lack of confidence in the French troops; on 17 October 1958, the French colonel Chevrau had given his support to Moro Naba Kougri.[55] On 24 April 1961, Yaméogo signed an accord about technical military assistance with France alone.[96] Subsequently, he demanded the surrender of the French base at Bobo-Dioulasso by 31 December 1961,[97] in favour of the Voltaic Armed Forces (FAV) which had been created on 1 November.[98]

Rapprochement with the Casablanca Group (1961–1962)

[edit]

Maurice Yaméogo was a fervent anti-communist.[99] In December 1960, he co-founded the Brazzaville group with the "moderate" leaders of Francophone Africa, which combined with Anglophone leaders in May 1961 as the Monrovia Group. The Brazzaville and Monrovia Groups were strongly opposed to the "progressivist" Casablanca Group.[100] In March 1961, the Brazzaville Group created the African and Malagasy Union (UAM), a resolutely anti-communist organisation which included a defense pact.[96] On 9 September 1961, Yaméogo succeeded in having Ouagadougou designated as the seat of the UAM's defense council and in having the Voltaic Albert Balima appointed secretary general.[101] In June 1961, Yaméogo was the first African head of state to visit Israel,[14] with which he signed a treaty of friendship and alliance.[101]

This did not mean an open break with the members of the Casablanca Group. Perhaps he saw this as a means of attracting American aid to his country. In any case, Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea was received at the capital in May 1961,[92] and Modibo Keïta of Mali in March 1962.[92] Relations with Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana were a top goal; Yaméogo went to Accra in May 1961 and hosted Nkrumah on 16 June.[102] In the resulting Tamalé accords, Upper Volta and Ghana agreed to a customs union similar to that which had been made with Côte d'Ivoire.[92][103] Yaméogo enthusiastically called for a shared constitution for the two countries and declared "Long live the future United States of Africa!"[102] Analysing the situation, the American ambassador to Upper Volta concluded that "Yaméogo is fairly pro-American, but he wants to be independent of France, which is to say that he needs American economic assistance." He thought in particular that Yaméogo was attempting to end the French economic monopoly; French goods cost several times the price of the Japanese goods which could be imported through Ghana.[104] The friendship between Yaméogo and Nkrumah was short lived. Yaméogo made up with Félix Houphouët-Boigny and the border controls with Ghana were re-established on 31 July 1962.[105] In July 1963, following a territorial dispute, Yaméogo denounced the "blatant expansionism" of Ghana.[102] A little later, relations with Mali deteriorated over the question of the border to the north of Gorom-Gorom.[102]

Return to the Ivoirien orbit (1962–1966)

[edit]On returning to the Ivoirien orbit, Yaméogo became a zealous supporter of Félix Houphouët-Boigny. In June 1965, after Sékou Touré of Guinea had called Houphouët-Boigny a supporter of French imperialism hostile to African unity,[106] Yaméogo appeared live on radio for close to an hour attacking the Guinean leader.[107] He declared:

Who is this Sékou, alias Touré, who wishes to speak of him in such a way? An arrogant, deceitful, jealous, envious, cruel, hypocritical, ungrateful and intellectually dishonest man... You are just a bastard among the bastards who populate the world. Once again, Sékou, you are a bastard of bastards.[106]

A warming of relations with France came to fruition in 1964, with the signing of two military agreements, the second of which, signed on 24 October, granted France "the triple right of flight over, encampment in, and transit through, Voltaic territory.".[96]

The following year in March and April, Yaméogo was the first African head of state invited to the White House by President Lyndon Johnson.[108] This honour, a complete surprise, was partially due to the fact that Yaméogo had a farm and so it was supposed that he would appreciate being hosted by Johnson on his ranch.[108] Taking advantage of the situation, Presidents Félix Houphouët-Boigny and Hamani Diori asked Yaméogo to submit a request for American financial aid to the president on their behalf.[109] Yaméogo returned from the United States with three billion CFA Francs to be split equally between himself, Houphouët-Boigny and Diori.[109] On Houphouët-Boigny's advice he placed his billion in a private Swiss bank account.[109] He used these funds to finance the legislative election campaign of 7 November 1965.[109] During his trip, Houphouët-Boigny had also entrusted him with another task. Taking advantage of the fact the Yaméogo was the only member of the Entente without a full defensive treaty with the French, he instructed Yaméogo to request a military treaty with the United States which would cover Côte d'Ivoire and Niger as well as Upper Volta in the event of a Chinese invasion, a threat which France was seeking to ignore.[110]

Yaméogo and Houphouët-Boigny also worked on a project of double nationality between Ivory Coast and Upper Volta. However, when Yaméogo left the presidency on January 3, 1966, Houphouët-Boigny abandoned this project of double nationality.

On October 17, 1965, Yaméogo married Suzanne de Monaco, a young Ivorian woman. Félix Houphouët-Boigny (President of Ivory Coast) and Hamani Diori (President of Niger) were the witnesses at his marriage. However, this union did not last long and Maurice married a third time with Jeannette.[111] Yaméogo had many children.

Internal affairs under Yaméogo

[edit]Degradation of the social climate

[edit]

With a strong Christian outlook, Yaméogo's dictatorial regime initially enjoyed the support of the Voltaic Catholic church.[112] In 1964, subsidies were removed for private schools (almost all of which were Catholic schools).[113] The clergy, whose finances were thereby threatened, became more critical.[113] The rupture became definitive in 1965. In that year, Yaméogo imprisoned his wife Félicité,[114] divorced her and married his mistress "Miss Côte d'Ivoire" Nathalie Monaco on 17 October in a sumptuous ceremony, at which President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Côte d'Ivoire and Hamani Diori of Niger served as groomsmen.[80] The happy couple honeymooned in the Caribbean and Brazil.[80] At the instruction of the head of the Voltaic church, cardinal Paul Zoungrana, the church invested all its moral authority in discrediting Yaméogo.[115] The religious climate declined still further when Yaméogo returned from his honeymoon and clumsily attacked charlatans and marabouts by radio, provoking the indignation of Muslims.[116]

Throughout his presidency, Yaméogo took measures against traditional chieftainship – undoubtedly motivated by republican ideals.[117] In January 1962, a decree forbade the display of all insignia recalling the customary chieftainships of the colonial period.[117] On 28 July 1964, a decree stated that should any village chieftainship fall vacant, it should be replaced by an election in which all inhabitants of the village on the electoral roll would be allowed to participate.[117] On 11 January 1965, a new decree ended government subsidies for chiefs.[118] These decisions were very well received in the west of the country where chiefs had not existed until introduced by the French.[118] In the east on the other hand, they provoked anger against Yaméogo.[118]

In turn, Yaméogo lost the support of the traditional elite, the unions, and the clergy. His excessive spending, such as the construction of a Party Palace,[119] did not help a situation which grew more dire in March and April 1965, when a measles epidemic struck the country as a result of a vaccine shortage.[120] In October, the shortage of classrooms and teachers made the beginning of the school year particularly difficult.[120] Many students had to be refused education,[120] although the enrolment rate was only 8%.[121] In December 1965, Yaméogo's project with Houphouët-Boigny to grant dual nationality to all citizens of Upper Volta and Côte d'Ivoire brought an end to his popularity. For most inhabitants of Upper Volta, this project implied a return to exploitation by Ivoiriens.[120]

Economic weakness

[edit]At independence, Upper Volta's economy was amongst the weakest in the world. The annual GDP was around 40 billion CFA francs,[122] almost entirely derived from subsistence activities.[123] 94% of the country's 3,600,000 inhabitants worked in agriculture, of which 85% focussed on the cultivation of food.[124] The tiny industrial sector employed around 4,000 people in some forty factories focussed on food processing.[121] There were only two power stations at this time, one in Ouagadougou and the other at Bobo-Dioulasso, with a maximum power of 3.5 megawatts and 3,000 customers.[121] Upper Volta has a total of 509 km of railway and 15,000 km of roads (only tar-sealed in a few urban centres).[125]

Despite efforts undertaken by the French authorities after 1954, Voltaic agriculture remained unproductive.[126] The planned establishment of a mentoring system and construction of hydro-electric dams between 1958 and 1962, co-financed by the French Aid and Cooperation Funds (FAC) and the Republic of Upper Volta, fell disappointingly short of its goals.[127] Undiscouraged, the state encouraged the establishment of co-operatives and credit unions,[128] and established a five-year plan for the period 1963 to 1967.[129] This ambitious plan predicted a sustained increase in agricultural production of 4.7% per year.[130] However, the cost of the plan, estimated at 1.5 billion CFA francs, prevented its implementation.[131] Yaméogo turned to Franco-Voltaic co-operation agreements to obtain aid from French companies for rural development.[124] These companies introduced new agricultural techniques for the cultivation of foodstuffs.[132] Improvement in nutrition was observed in areas of dietary deficit.[133] These efforts, along with a guaranteed, pre-announced price for agriculture, led to an increase in the production of cotton from 8,000 tonnes in 1963 to 20,000 tonnes in 1967.[132]

Cotton had a growing role in Upper Volta's exports, which reached 3.68 billion CFA francs in 1965.[134] Two-thirds of their value derived from livestock.[135] Despite being fairly mineral poor, the country exported 687 million CFA francs of unrefined gold between 1961 and 1963.[131] It is notable that Upper Volta was the only country in Africa whose main export partners were other African states.[136] Its main export partner was Côte d'Ivoire, although Ghana took the role in 1963 with 40.5% of Upper Volta's exports, before being relegated to second place in 1965 with 17.6%.[136] France, the third most important export partner of Upper Volta, was the source of 52% of the 9.169 billion CFA francs worth of imported products in 1965.[134] In 1965 the balance of trade was very negative, with a deficit of 5.489 billion CFA francs.

Austerity plans

[edit]

Throughout his presidency, Yaméogo sought every opportunity to obtain extra resources, much of which he was granted free of charge. Through subsidies, the French treasury gifted him 1.7 billion CFA francs.[137] Ghana advanced him a customs rebate of 1.1177 billion in 1961.[137] The Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) granted him 600 million in budgetary support.[137] But all this was insufficient to meet the state's budgetary shortfall, which increased after the departure of French troops in 1961. Yaméogo met this with loans and the treasury's cash reserves.[137] At the end of 1965, after five years of independence, Upper Volta's budget deficit exceeded 4.5 billion CFA francs.[138]

Therefore, in 1964, austerity measures were introduced.[139] An allowance has been made on special duty allowances, foreign embassies were reduced, and the representational allowance of the president was reduced from 18 to 9 million CFA francs.[139] The resulting savings came to 250 million CFA francs.[139] For the 1965 budget, Yaméogo decided to take more draconian measures. Payments to chiefs and subsidies for private schools were cancelled.[139] Monthly family allowances were reduced from 2,500 to 1,500 CFA francs per child and limited to families with less than six children.[139] These unpopular measures allowed him to reduce the budget deficit by 4.5%.[139] Encouraged by these results, Yaméogo appointed a young, French-educated technocrat, Raphaël Medah, in charge of finance on 8 December 1965.[140] He intended to:

- increase the budgetary revenue by levying a 10% flat tax on income (IFR)[140] and suppressing the preferential tariff on Ivoirien imports.[119]

- reduce state expenditures, by suppressing all the chiefs of cabinet, blocking all pay increases for two years, and limiting government cars to ministers alone.[119]

- reduce the budget deficit by cutting the pensions of old veterans by 16% and lowering family grants from 1,500 ti 750 CFA francs.

But the true measure was the reduction by 20% of all the salaries of civil servants with the fall by 10% of scheduled taxes.[140] This financial austerity plan was, ultimately the cause of the regime's downfall.

Fall from power

[edit]Popular uprising on 3 January 1966

[edit]Although autonomous unions had officially been resolved in May 1964, they reformed in December 1965 as an inter-union front led by Joseph Ouédraogo, in order to denounce Yaméogo's austerity plans. Yaméogo was then in Côte d'Ivoire to discuss the dual nationality agreement.[141] As the situation escalated, the director of the cabinet, Adama André Compaoré called Yaméogo to inform him.[141] He did not recognise the seriousness of the situation and assumed that there was no reason to worry.[141] On 31 December, the unionists organised a meeting at the labour council, where they called for a general strike on 3 January 1966.[142] This gathering had been forbidden by the minister of the interior, Denis Yaméogo, and was dispersed by the police forces.[142] Maurice Yaméogo returned to Upper Volta on the same day and celebrated New Year's Eve without concern for the mounting troubles.[141]

On 1 January 1966, Yaméogo finally decided to proclaim a state of emergency: all protests were forbidden and the strikes were declared illegal.[143] In order to discredit the inter-union front's actions, Joseph Ouédraogo was accused of espionage on behalf of the communists.[142] Officials were threatened with collective dismissal if they participated in the movement.[144] Finally, he demanded that religious authorities intervene to calm the situation.[144] They refused since they were not on good terms with Yaméogo. Along with the traditional elite, they gave their support to the movement.[145]

Even so, the 1st and 2 January were relatively calm.[141] It was only on the night of the 2nd that events began to come to a head.[141] Yaméogo failed in his efforts to arrest the leaders of the inter-union front at the labour council.[141] He ordered several armoured cars to be stationed around the palace and garrisoned the key public buildings, particularly the radio stations.[144] The protest began in the morning of 3 January. It seems to have been Jacqueline Ki-Zerbo, the wife of Joseph Ki-Zerbo, who opened the protests with her schoolgirls.[146] Carrying signs calling for "Bread, water, and democracy," they were soon joined by the students of the Philippe Zinda Kaboré high school.[146] These students were soon joined by more than 100,000 people of Ouagadougou,[14] including numerous officials calling for the cancellation of the 20% cut to their salaries. The protest was not violent.[141][147] Allegedly, the police themselves took part in the protests.[147] Late in the afternoon, Yaméogo made it known to the protesters by means of his chief of staff, lieutenant-colonel Sangoulé Lamizana, that he would cancel the 20% cut and retain the existing rate of subsidies.[148] But the situation had moved beyond the demands of Joseph Ouédraogo's unionists[149] and the crowd, led by the historian Joseph Ki-Zerbo called for the resignation of the President, who was cut off in camp Guillaume Ouédraogo.[148] Finally, to resolve the situation, the leading protesters appealed to the army to take power.[148]

Resignation

[edit]After several hours of negotiations, Maurice Yaméogo went on the radio at 4 pm[150] and announced his decision to hand power over to lieutenant-colonel Sangoulé Lamizana:

Contrairement à ce que l'on peut croire, je suis le premier réjoui - et mes ministres après moi - de la manière la plus pacifique dont les choses se sont résolues. Si depuis plus de quatre jours, notre capitale d'habitude si pacifique a connu un tel échauffement et que heureusement rien ne se soit produit sur le plan de la perte de vies humaines, c'est parce que là encore, bien que possédant les attributs du pouvoir, nous n'avons pas voulu user de quoi que ce soit pour qu'un jour, on puisse dire que la Haute-Volta a perdu l'une de ses grandes vertus qui est le respect de soi-même, l'amour entre ses frères. Et c'est pour quoi je suis heureux que le chef d'état-major général, entouré de tous ses officiers, ait pu, en parfaite harmonie avec moi-même, pour que l'histoire de notre pays puisse continuer à aller de l'avant, réaliser de façon si pacifique ce que j'appellerais ce transfert de compétences. L'équipe qui s'en va n'éprouve aucune rancœur croyez-moi bien. |

Contrary to what one might believe, I am the first to welcome (and my ministers with me) the peaceful manner in which things have been resolved. If after more than four days, our usually peaceful capital has experienced a rise in temperature and fortunately nothing in the way of loss of life, it is because once again, although holding power, we have not wished to do anything for the sake of a single day, that would allow it to be said that Upper Volta had destroyed one of its great virtues: our self-respect and brotherly love. And it is for this reason that I am glad that the chief of the general staff, supported by all his officers, has, in perfect harmony with myself, so that the history of our country can continue to move forward, completed in a peaceful fashion what I would call the transfer of competences. The outgoing team does not feel any rancour, believe me. |

| —Maurice Yaméogo[150] |

The Army was in control; the Constitution was suspended, the National Assembly was dissolved, and Lt. Col. Sangoulé Lamizana was placed at the head of a government essentially run by senior army officers. The army remained in power for four years, and on June 14, 1970, the Voltans ratified a new Constitution that established a four-year transition period toward complete civilian rule. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s as president of military or mixed civil-military governments. After a conflict arising over the 1970 Constitution, a new constitution was written and approved in 1977, and Lamizana was reelected through open elections in 1978.[151]

There are two different accounts of Yaméogo's decision to resign. According to Frédéric Guirma who interviewed Sangoulé Lamizana in 1967, Maurice Yaméogo had ordered the chief of the FAV to restore order by firing on the crowd.[152] Lamizana's reported to have replied that before an army would ever fire on its people, the order must be made in writing.[152] Yaméogo refused to do this and continued to insist that the chief do as instructed.[152] Lamizana then consulted with his officers, the majority of which were opposed.[153] Yaméogo then decided to announce a "transfer of competences" in ambiguous terms, intending to resume control once the crisis was over.[154] But as a result of popular pressure, he had to resign himself to signing his full resignation.[154]

Yaméogo told the historian Ibrahim Baba Kaké that he had resigned in order to prevent any bloodshed.[152][155] On the radio broadcast of Alain Foka's Archives d’Afrique, dedicated to Maurice Yaméogo, Sangoulé Lamizana declared that he had never received an order to fire on the protesters,[14] supporting Yaméogo's account of events. Lamizana, in tears, had reluctantly agreed to take power.[152]

After the presidency

[edit]Imprisonment and disenfranchisement (1966–1970)

[edit]

Against the advice of the unionists, Lamizana had the deposed president escorted to Koudougou.[156] A little later, his supporters decided to enter the capital in order to contest the decision.[156] A military force was immediately sent out to maintain order.[156] Finally, to prevent any further incidents, the government placed Yaméogo under house arrest in Ouagadougou on 6 January.[156] Yaméogo took this detention very badly, to the point of attempting to take his own life in December 1966.[157] His friend Félix Houphouët-Boigny was moved by this and put active pressure on the French government to demand Yaméogo's release.[158] On 28 April 1967, Yaméogo was brought before a special tribunal charged with investigating his years in power.[158] On 5 August 1967, his son Hermann Yaméogo attempted to launch a coup d'état to free him, which failed.[158]

After these events, Charles de Gaulle boycotted Sangoulé Lamizana in order to obtain Yaméogo's release.[158] He received a promise.[158] But time passed and in January 1968, Yaméogo made a second attempt at suicide by drinking a strong dose of Nivaquine.[157] Finally, on 8 May 1969,[3] Yaméogo was condemned in a closed court to five years of forced labour and banishment for life with the loss of all civil rights. A few days after this verdict, Lamizana issued a presidential pardon and on 5 August 1970, Yaméogo was set free.[156]

In the course of these events, Yaméogo's property had been seized.[159] This included the palace which he had built in his hometown of Koudougou in 1964, officially as a result of the alleged seizure of his villa in the French Riviera and thanks to a French private bank loan.[159] The palace had cost 59 million CFA francs.[159] After his fall, Yaméogo's wife Nathalie Monaco had left him.[3] he remarried for a third time to Jeannette Ezona Kansolé.[160]

Final success, imprisonment and rehabilitation (1970–1993)

[edit]Maurice Yaméogo continued to participate in the political life of his country using his son Hermann Yaméogo as an intermediary.[161] In 1977 he created the National Union for the Defense of Democracy (UNDD), based on nostalgia for the first republic.[161] In the legislative elections of 1977, the UNDD became the second-largest political party in the country after the UDV-RDA.[161] In the presidential elections of 1978, the party fielded the banker Macaire Ouédraogo as their candidate, since Maurice Yaméogo was barred from running due to his disenfranchisement and Hermann Yaméogo was too young to run.[161] Ouédraogo was defeated by Lamizana in the second round on 28 May 1978.[161]

In 1980, Upper Volta suffered several coups d'état. In May 1983, Maurice Yaméogo organised a protest in favour of president Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo.[156] On 4 August 1983, Ouédraogo was overthrown by the National Council of the Revolution (CNR) commanded by Thomas Sankara. The country was renamed Burkina Faso. On 9 November 1983,[161] Yaméogo was brought to the Conseil de l'Entente by Sankara's men in order to be shot.[151][156] He survived thanks to Blaise Compaoré who proposed his imprisonment at the Pô military camp.[161] On the first anniversary of Sankara's revolution in 1984, Maurice Yaméogo was set free.[156] On this occasion, he declared his allegiance to Thomas Sankara on radio.[156]

After some time in Koudougou, Yaméogo settled in Côte d'Ivoire in spring 1987.[3] He enjoyed a role as an intermediary between the government of Burkina Faso and president Félix Houphouët-Boigny.[3] In May 1991, Blaise Compaoré, now president of Burkina Faso, ordered his rehabilitation.[3] This decision followed a letter written to him by Yaméogo in 1987 seeking the final settlement of the confiscation of his property.[156] Yaméogo recovered his civil rights and his property.[111] In September 1993, Yaméogo became very sick and was taken to Paris to receive treatment.[156] Because of the seriousness of his condition, he decided to return to Koudougou in order to live out his last days.[156] He died on 15 September on the flight home.[156] His funeral on 17 September was attended by many of the region's political personalities, including Alassane Ouattara (Prime Minister of Ivory Coast) and Laurent Dona Fologo (Secretary general of PDCI-RDA).[111][156]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ États africains d'expression française et République malgache, Paris, Éditions Julliard, 1964, p. 73

- ^ a b c Alfred Yambangba Sawadogo, Afrique: la démocratie n'a pas eu lieu, Paris, Éditions L'Harmattan, 2008, p. 30

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jean-Pierre Bejot, " Quand la Côte d'Ivoire et la Haute-Volta (devenue Burkina Faso) rêvaient de la double nationalité ", La Dépêche Diplomatique 16 October 2002, Online on lefaso.net

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, Comment perdre le pouvoir ? Le cas de Maurice Yameogo, Paris, Éditions Chaka, coll. « Afrique contemporaine », p.23

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 24

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 25

- ^ Alfred Yambangba Sawadogo, op. cit., p. 31

- ^ a b c Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 27

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 28

- ^ a b c d LA PETITE ACADEMIE. (2004). Detail sur la personalite selectionnee. LA PETITEACADEMIE. Retrieved March 19, 2006 from http://www.petiteacademie.gov.bf/Personnalite.asp?CodePersonnalite=216[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 29

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 30

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 31

- ^ a b c d Alain Foka, " Maurice Yaméogo " In Archives d'Afrique (émission radiophonique de RFI), 2e partie, 18 May 2007

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 32

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 33

- ^ La petite Académie, Liste des conseillers généraux de la première assemblée territoriale de Haute-Volta de 1946 à 1952 Online on petiteacademie.gov.bf Archived 2009-08-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nationale, Assemblée. "Formulaire de recherche dans la base de données des députés français depuis 1789 - Assemblée nationale".

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 46

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao (ed.), Burkina Faso cent ans d'histoire, 1895-1995, t.2, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 2003, p. 1480

- ^ a b Roger Bila Kaboré, Histoire politique du Burkina Faso: 1919-2000, Paris, Éditions L’Harmattan, 2002, p. 30

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 55

- ^ a b Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 31

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 39

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 58

- ^ a b c Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 59

- ^ Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), La Haute-Volta coloniale: témoignages, recherches, regards, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1995, p. 436

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 60

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 61

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 65

- ^ "Joseph Conombo". Assemblée nationale.

- ^ Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 33

- ^ "Nazi Boni". Assemblée nationale.

- ^ a b c Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 72

- ^ René Otayek, F. Michel Sawadogo, et Jean-Pierre Guingané, Le Burkina entre révolution et démocratie (1983-1993), Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1996, p. 327

- ^ a b Joseph-Roger de Benoist, L'Afrique occidentale française de la Conférence de Brazzaville (1944) à l'indépendance (1960), Dakar, Nouvelles éditions africaines, 1982, p. 219

- ^ Joseph Issoufou Conombo, et Monique Chajmowiez, Acteur de mon temps: un voltaïque dans le XXe siècle, Paris, Éditions L'Harmattan, 2003, p. 178

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 78

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 79

- ^ Claudette Savonnet-Guyot, État et sociétés au Burkina: essai sur le politique africain: essai sur le politique africain, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1986, p. 137

- ^ Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p. 434

- ^ a b Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p. 438

- ^ a b c Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 37

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 85

- ^ a b c Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 39

- ^ Janda, K. (1980). UPPER VOLTA: The Party System in 1950–1956 and 1957–1962.Political Parties: A Cross-National Survey Retrieved March 26, 2006 from "Party politics in Upper Volta, 1950-1962". Archived from the original on 2006-07-22. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 88

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 89

- ^ a b c Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 40

- ^ "La Haute-Volta, du référendum à l'indépendance". Burkina Faso: Cent ans d'histoire, 1895-1995. 1. Éditions Karthala: 1009. 2003. ISBN 9782845864313. HV2003.

- ^ a b Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 41

- ^ a b Bendre. (2005). Les acrobaties politiques en Haute Volta a la veille des indépendances. Bendre. Retrieved March 19, 2006 from http://www.bendre.africa-web.org/article.php3?id_article=985[permanent dead link]

- ^ Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 42

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao, Burkina Faso : cent ans d'histoire, 1895-1995: actes du premier colloque international sur l'histoire du Burkina, Ouagadougou, 12-17 décembre 1996 (Université De Ouagadougou, 2003), p.1008

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1049

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1008

- ^ a b c d e Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.444

- ^ a b c d Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1016

- ^ a b Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.445

- ^ a b c d e f Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.446

- ^ a b c L'Année politique, économique, sociale et diplomatique en France, Paris, PUF, 1960, p.268

- ^ a b c Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1021

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.114-115

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1025

- ^ Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.503

- ^ a b c Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1023

- ^ a b c d e Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1026

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1027

- ^ a b c Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1028

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1753

- ^ Michel Izard and Jean du Bois de Gaudusson, " Burkina Faso " In Encyclopédie Universalis 2008

- ^ "Gérard Kango Ouédraogo". Assemblée nationale.

- ^ Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p.61

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.127

- ^ a b c Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p.62

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.128

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.132

- ^ Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p.63

- ^ Pascal Zagré, Les politiques économiques du Burkina Faso: une tradition d'ajustement structurel, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1994, p.47

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Lejeal, Le Burkina Faso, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 2002, p.79

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.135

- ^ Charles Kabeya Muase, Syndicalisme et démocratie en Afrique noire: l'expérience du Burkina Faso (1936-1988), Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1989, p.68

- ^ Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p.69

- ^ a b Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p.42

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.154

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1013

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga & Oumarou Nao (ed.), op. cit., t.1, p.1014

- ^ a b Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.501

- ^ a b Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.70

- ^ Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.71

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.161

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.16

- ^ Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.504

- ^ Gabriel Massa, et Y. Georges Madiéga (dir.), op. cit., p.498

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1048

- ^ a b c Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao (ed.), op. cit., t.1, p.1047

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.1, p.1046

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.124

- ^ Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.158

- ^ Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.160

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p.125

- ^ a b c d Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.163

- ^ Bernard Gérardin, Le développement de la Haute-Volta: avec un avant-propos de G. de Bernis, Paris, Institut de science économique appliquée, 1963, p.39

- ^ Pierre-Michel Durand, L'Afrique et les relations franco-américaines des années soixante, Paris, Éditions L'Harmattan, 2007, p.99

- ^ Eureka (trimestriel), recueil des numéros 41 à 48, Ouagadougou, CNRST, 2002, p.55

- ^ a b Joachim Vokouma, "Amadou '’Balaké'’, la voix d'or du Burkina ", 11 décembre 2006, Online on lefaso.net

- ^ Pierre-Michel Durand, op. cit., p. 219

- ^ a b Pierre-Michel Durand, op. cit., p. 306

- ^ a b c d Alain Saint Robespierre, " Banques suisses: Où est passé le milliard de Maurice Yaméogo ? ", L'Observateur Paalga, 30 mai 2007, online on lefaso.net

- ^ Pierre-Michel Durand, op. cit., p.307

- ^ a b c Lefaso.net (2006). Quand la Cote d’Ivoire et la Haute-Volta (devenue Bukina Faso) revaient de la "double nationalite". Retrieved March 26, 2006, from http://www.lefaso.net/article.php3?id_article=136/ Archived 2006-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ François Constantin and Christian Coulon, Religion et transition démocratique en Afrique, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1997, p. 229

- ^ a b François Constantin et Christian Coulon, op. cit., p. 230

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 137

- ^ Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p. 72

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 138

- ^ a b c Claude Hélène Perrot and François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, Le retour des rois: les autorités traditionnelles et l'état en Afrique contemporaine, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1999, p. 235

- ^ a b c Claude Hélène Perrot et François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, op. cit., p. 236

- ^ a b c Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p. 60

- ^ a b c d Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p. 64

- ^ a b c Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p. 39

- ^ Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.38

- ^ Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.49

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao (ed.), op. cit., t.2, p.1600

- ^ Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.40

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1599

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1595-1596

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1597

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1598

- ^ Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.53

- ^ a b Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p.66

- ^ a b Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1603

- ^ Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga, et Oumarou Nao (dir.), op. cit., t.2, p.1604

- ^ a b Direction du commerce, Commerce extérieur et balance commerciale de la République Haute-Volta, Ouagadougou, Bureau d'études et de documentation, 1970, p.2

- ^ Direction du commerce, op. cit., p.5

- ^ a b Direction du commerce, op. cit., p.7

- ^ a b c d Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.56

- ^ Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.55

- ^ a b c d e f Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.58

- ^ a b c Pascal Zagré, op. cit., p.59

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mahorou Kanazoe, " Evénéments du 3 janvier 1966: Le '’Dirca'’ de Maurice Yaméogo à cœur ouvert ", Le pays, 2 janvier 2008, online on lefaso.net

- ^ a b c Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p.77

- ^ Frédéric Lejeal, op. cit., p.81

- ^ a b c Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p. 78

- ^ Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p. 79

- ^ a b Roger Bila Kaboré, op. cit., p. 65

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 143

- ^ a b c Charles Kabeya Muase, op. cit., p. 82

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 146

- ^ a b Alain Foka, op. cit., 1re partie

- ^ a b Historycentral. (2006). BURKINA FASO Retrieved March 19, 2006 from "Burkino History". Archived from the original on 2006-03-27. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- ^ a b c d e Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 144

- ^ Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 145

- ^ a b Frédéric Guirma, op. cit., p. 147

- ^ Lefaso.net. (2009). Général Sangoulé Lamizana: Un non-assoiffé de pouvoir Retrieved December 11, 2009 from http://www.lefaso.net/spip.php?article7545

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Alain Foka, op. cit., 3e partie

- ^ a b Commission de publication des documents diplomatiques français, Documents diplomatiques français, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 2008, p. 228

- ^ a b c d e Jean-Pierre Bejot, «Gal A. Sangoulé Lamizana, portrait d’un combattant (2) », La Dépêche Diplomatique, Online on lefaso.net

- ^ a b c Alain Saint Robespierre, «Koudougou: Dans les profondeurs des ruines présidentielles », L'Observateur Paalga, 30 mai 2007, Online on lefaso.net

- ^ « Ruines présidentielles de Koudougou: Complément d’informations », L'Observateur Paalga, 1 June 2007, Online on lefaso.net

- ^ a b c d e f g Jean-Pierre Bejot, « Hermann Yaméogo, un "héritier" joue la déstabilisation du Burkina (2) », La Dépêche Diplomatique, Online on lefaso.net

Bibliography

[edit]- Charles Kabeya Muase, Syndicalisme et démocratie en Afrique noire: l'expérience du Burkina Faso (1936-1988), Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1989, 252 p. ISBN 2865372413

- Frédéric Guirma, Comment perdre le pouvoir ? Le cas de Maurice Yameogo, Paris, Éditions Chaka, coll. « Afrique contemporaine », 1991, 159 p. ISBN 2907768123

- Pascal Zagré, Les politiques économiques du Burkina Faso: une tradition d'ajustement structurel, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1994, 244 p. ISBN 2865375358

- Gabriel Massa and Y. Georges Madiéga (ed.), La Haute-Volta coloniale: témoignages, recherches, regards, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 1995, 677 p. ISBN 2865374807

- Frédéric Lejeal, Le Burkina Faso, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 2002, 336 p. ISBN 2845861435

- Roger Bila Kaboré, Histoire politique du Burkina Faso: 1919-2000, Paris, Éditions L’Harmattan, 2002, 667 p. ISBN 2747521540

- Yénouyaba Georges Madiéga and Oumarou Nao (ed.), Burkina Faso cent ans d’histoire, 1895-1995, 2 volumes, Paris, Éditions Karthala, 2003, 3446 p. ISBN 2845864310

- Pierre-Michel Durand, L’Afrique et les relations franco-américaines des années soixante, Paris, Éditions L’Harmattan, 2007, 554 p. ISBN 2296046053

- 1921 births

- 1993 deaths

- People from Centre-Ouest Region

- People of French West Africa

- Burkinabé politicians

- Heads of state of Burkina Faso

- Foreign ministers of Burkina Faso

- Burkinabé Roman Catholics

- Rassemblement Démocratique Africain politicians

- French Confederation of Christian Workers members

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Heads of government who were later imprisoned

- Mossi people

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from animism