Rockwell B-1 Lancer

| B-1 Lancer | |

|---|---|

A B-1B flying with 20-degree wing sweep | |

| General information | |

| Type | Supersonic strategic heavy bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Original: North American Rockwell/Rockwell International Current contractor: Boeing[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 104[a] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1973–1974, 1983–1988 |

| Introduction date | 1 October 1986 |

| First flight | 23 December 1974 |

The Rockwell B-1 Lancer[b] is a supersonic variable-sweep wing, heavy bomber used by the United States Air Force. It has been nicknamed the "Bone" (from "B-One").[2][3] As of 2024[update], it is one of the United States Air Force's three strategic bombers, along with the B-2 Spirit and the B-52 Stratofortress. Its 75,000-pound (34,000 kg) payload is the heaviest of any U.S. bomber.[4]

The B-1 was first envisioned in the 1960s as a bomber that would combine the Mach 2 speed of the B-58 Hustler with the range and payload of the B-52, ultimately replacing both. After a long series of studies, North American Rockwell (subsequently renamed Rockwell International, B-1 division later acquired by Boeing) won the design contest for what emerged as the B-1A. Prototypes of this version could fly Mach 2.2 at high altitude and long distances at Mach 0.85 at very low altitudes. The program was canceled in 1977 due to its high cost, the introduction of the AGM-86 cruise missile that flew the same basic speed and distance, and early work on the B-2 stealth bomber.

The program was restarted in 1981, largely as an interim measure due to delays in the B-2 stealth bomber program. The B-1A design was altered, reducing top speed to Mach 1.25 at high altitude, increasing low-altitude speed to Mach 0.96, extensively improving electronic components, and upgrading the airframe to carry more fuel and weapons. Dubbed the B-1B, deliveries of the new variant began in 1985; the plane formally entered service with Strategic Air Command (SAC) as a nuclear bomber the following year. By 1988, all 100 aircraft had been delivered.

With the disestablishment of SAC and its reassignment to the Air Combat Command in 1992, the B-1B's nuclear capabilities were disabled and it was outfitted for conventional bombing. It first served in combat during Operation Desert Fox in 1998 and again during the NATO action in Kosovo the following year. The B-1B has supported U.S. and NATO military forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. As of 2021 the Air Force has 45 B-1Bs.[5] The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider is to begin replacing the B-1B after 2025; all B-1s are planned to be retired by 2036.[6]

Development

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1955, the USAF issued requirements for a new bomber combining the payload and range of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress with the Mach 2 maximum speed of the Convair B-58 Hustler.[7] In December 1957, the USAF selected North American Aviation's B-70 Valkyrie for this role, a six-engine bomber that could cruise at Mach 3 at high altitude (70,000 ft or 21,000 m).[8][9] Soviet Union interceptor aircraft, the only effective anti-bomber weapon in the 1950s,[10] were already unable to intercept the high-flying Lockheed U-2;[11] the Valkyrie would fly at similar altitudes, but much higher speeds, and was expected to fly right by the fighters.[10]

By the late 1950s, however, anti-aircraft surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) could threaten high-altitude aircraft,[12] as demonstrated by the 1960 downing of Gary Powers' U-2.[13] The USAF Strategic Air Command (SAC) was aware of these developments and had begun moving its bombers to low-level penetration even before the U-2 incident. This tactic greatly reduces radar detection distances through the use of terrain masking; using features of the terrain like hills and valleys, the line-of-sight from the radar to the bomber can be broken, rendering the radar (and human observers) incapable of seeing it.[14] Additionally, radars of the era were subject to "clutter" from stray returns from the ground and other objects, which meant a minimum angle existed above the horizon where they could detect a target. Bombers flying at low altitudes could remain under these angles simply by keeping their distance from the radar sites. This combination of effects made SAMs of the era ineffective against low-flying aircraft.[14][15] The same effects also meant that low-flying aircraft were difficult to detect by higher-flying interceptors, since their radar systems could not readily pick out aircraft against the clutter from ground reflections (lack of look-down/shoot-down capability).

The switch from high-altitude to low-altitude flight profiles severely affected the B-70, the design of which was tuned for high-altitude performance. Higher aerodynamic drag at low level limited the B-70 to subsonic speed while dramatically decreasing its range.[12] The result would be an aircraft with somewhat higher subsonic speed than the B-52, but less range. Because of this, and a growing shift to the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force, the B-70 bomber program was cancelled in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy,[10][16] and the two XB-70 prototypes were used in a supersonic research program.[17]

Although never intended for the low-level role, the B-52's flexibility allowed it to outlast its intended successor as the nature of the air war environment changed. The B-52's huge fuel load allowed it to operate at lower altitudes for longer times, and the large airframe allowed the addition of improved radar jamming and deception suites to deal with radars.[18] During the Vietnam War, the concept that all future wars would be nuclear was turned on its head, and the "big belly" modifications increased the B-52's total bomb load to 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg),[19] turning it into a powerful tactical aircraft which could be used against ground troops along with strategic targets from high altitudes.[15] The much smaller bomb bay of the B-70 would have made it much less useful in this role.

Design studies and delays

[edit]Although effective, the B-52 was not ideal for the low-level role. This led to a number of aircraft designs known as penetrators, which were tuned specifically for long-range low-altitude flight. The first of these designs to see operation was the supersonic F-111 fighter-bomber, which used variable-sweep wings for tactical missions.[20] A number of studies on a strategic-range counterpart followed.

The first post-B-70 strategic penetrator study was known as the Subsonic Low-Altitude Bomber (SLAB), which was completed in 1961. This produced a design that looked more like an airliner than a bomber, with a large swept wing, T-tail, and large high-bypass engines.[21] This was followed by the similar Extended Range Strike Aircraft (ERSA), which added a variable-sweep wing, then en vogue in the aviation industry. ERSA envisioned a relatively small aircraft with a 10,000-pound (4,500 kg) payload and a range of 10,070 miles (16,210 km) including 2,900 miles (4,700 km) flown at low altitudes. In August 1963, the similar Low-Altitude Manned Penetrator design was completed, which called for an aircraft with a 20,000-pound (9,100 kg) bomb load and somewhat shorter range of 8,230 miles (13,240 km).[22][23]

These all culminated in the October 1963 Advanced Manned Precision Strike System (AMPSS), which led to industry studies at Boeing, General Dynamics, and North American (later North American Rockwell).[24][25] In mid-1964, the USAF had revised its requirements and retitled the project as Advanced Manned Strategic Aircraft (AMSA), which differed from AMPSS primarily in that it also demanded a high-speed high-altitude capability, similar to that of the existing Mach 2-class F-111.[26] Given the lengthy series of design studies, North American Rockwell engineers joked that the new name actually stood for "America's Most Studied Aircraft".[27]

The arguments that led to the cancellation of the B-70 program had led some to question the need for a new strategic bomber of any sort. The USAF was adamant about retaining bombers as part of the nuclear triad concept that included bombers, ICBMs, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) in a combined package that complicated any potential defense. They argued that the bomber was needed to attack hardened military targets and to provide a safe counterforce option because the bombers could be quickly launched into safe loitering areas where they could not be attacked. However, the introduction of the SLBM made moot the mobility and survivability argument, and a newer generation of ICBMs, such as the Minuteman III, had the accuracy and speed needed to attack point targets. During this time, ICBMs were seen as a less costly option based on their lower unit cost,[28] but development costs were much higher.[12] Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara preferred ICBMs over bombers for the Air Force portion of the deterrent force[29] and felt a new expensive bomber was not needed.[30][31] McNamara limited the AMSA program to studies and component development beginning in 1964.[31]

Program studies continued; IBM and Autonetics were awarded AMSA advanced avionics study contracts in 1968.[31][32] McNamara remained opposed to the program in favor of upgrading the existing B-52 fleet and adding nearly 300 FB-111s for shorter range roles then being filled by the B-58.[15][31] He again vetoed funding for AMSA aircraft development in 1968.[32]

B-1A program

[edit]

President Richard Nixon reestablished the AMSA program after taking office, keeping with his administration's flexible response strategy that required a broad range of options short of general nuclear war.[34] Nixon's Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird, reviewed the programs and decided to lower the numbers of FB-111s, since they lacked the desired range, and recommended that the AMSA design studies be accelerated.[34] In April 1969, the program officially became the B-1A.[15][34] This was the first entry in the new bomber designation series, created in 1962. The Air Force issued a request for proposals in November 1969.[35]

Proposals were submitted by Boeing, General Dynamics and North American Rockwell in January 1970.[35][36] In June 1970, North American Rockwell was awarded the development contract.[35] The original program called for two test airframes, five flyable aircraft, and 40 engines. This was cut in 1971 to one ground and three flight test aircraft.[37] The company changed its name to Rockwell International and named its aircraft division North American Aircraft Operations in 1973.[38] A fourth prototype, built to production standards, was ordered in the fiscal year 1976 budget. Plans called for 240 B-1As to be built, with initial operational capability set for 1979.[39]

Rockwell's design had features common to the F-111 and XB-70. It used a crew escape capsule, that ejected as a unit to improve crew survivability if the crew had to abandon the aircraft at high speed. Additionally, the design featured large variable-sweep wings in order to provide both more lift during takeoff and landing, and lower drag during a high-speed dash phase.[40] With the wings set to their widest position the aircraft had a much better airfield performance than the B-52, allowing it to operate from a wider variety of bases. Penetration of the Soviet Union's defenses would take place at supersonic speed, crossing them as quickly as possible before entering the more sparsely defended interior of the country where speeds could be reduced again.[40] The large size and fuel capacity of the design would allow the "dash" portion of the flight to be relatively long.

In order to achieve the required Mach 2 performance at high altitudes, the exhaust nozzles and air intake ramps were variable.[41] Initially, it had been expected that a Mach 1.2 performance could be achieved at low altitude, which required that titanium be used in critical areas in the fuselage and wing structure. The low altitude performance requirement was later lowered to Mach 0.85, reducing the amount of titanium and therefore cost.[37] A pair of small vanes mounted near the nose are part of an active vibration damping system that smooths out the otherwise bumpy low-altitude ride.[42] The first three B-1As featured the escape capsule that ejected the cockpit with all four crew members inside. The fourth B-1A was equipped with a conventional ejection seat for each crew member.[43]

The B-1A mockup review occurred in late October 1971; this resulted in 297 requests for alteration to the design due to failures to meet specifications and desired improvements for ease of maintenance and operation.[44] The first B-1A prototype (Air Force serial no. 74–0158) flew on 23 December 1974.[45] As the program continued the per-unit cost continued to rise in part because of high inflation during that period. In 1970, the estimated unit cost was $40 million, and by 1975, this figure had climbed to $70 million.[46]

New problems and cancellation

[edit]

In 1976, Soviet pilot Viktor Belenko defected to Japan with his MiG-25 "Foxbat".[47] During debriefing he described a new "super-Foxbat" (almost certainly referring to the MiG-31) that had look-down/shoot-down radar in order to attack cruise missiles. This would also make any low-level penetration aircraft "visible" and easy to attack.[48] Given that the B-1's armament suite was similar to the B-52, and it then appeared no more likely to survive Soviet airspace than the B-52, the program was increasingly questioned.[49] In particular, Senator William Proxmire continually derided the B-1 in public, arguing it was an outlandishly expensive dinosaur. During the 1976 federal election campaign, Jimmy Carter made it one of the Democratic Party's platforms, saying "The B-1 bomber is an example of a proposed system which should not be funded and would be wasteful of taxpayers' dollars."[50]

When Carter took office in 1977 he ordered a review of the entire program. By this point the projected cost of the program had risen to over $100 million per aircraft, although this was lifetime cost over 20 years. He was informed of the relatively new work on stealth aircraft that had started in 1975, and he decided that this was a better approach than the B-1. Pentagon officials also stated that the AGM-86 Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) launched from the existing B-52 fleet would give the USAF equal capability of penetrating Soviet airspace. With a range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km), the ALCM could be launched well outside the range of any Soviet defenses and penetrate at low altitude like a bomber (with a much lower radar cross-section (RCS) due to smaller size), and in much greater numbers at a lower cost.[51] A small number of B-52s could launch hundreds of ALCMs, saturating the defense. A program to improve the B-52 and develop and deploy the ALCM would cost at least 20% less than the planned 244 B-1As.[50]

On 30 June 1977, Carter announced that the B-1A would be canceled in favor of ICBMs, SLBMs, and a fleet of modernized B-52s armed with ALCMs.[39] Carter called it "one of the most difficult decisions that I've made since I've been in office." No mention of the stealth work was made public with the program being top secret, but it is now known that in early 1978 he authorized the Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) project, which eventually led to the B-2 Spirit.[52]

Domestically, the reaction to the cancellation was split along partisan lines. The Department of Defense was surprised by the announcement; it expected that the number of B-1s ordered would be reduced to around 150.[53] Congressman Robert Dornan (R-CA) claimed, "They're breaking out the vodka and caviar in Moscow."[54] However, it appears the Soviets were more concerned by large numbers of ALCMs representing a much greater threat than a smaller number of B-1s. Soviet news agency TASS commented that "the implementation of these militaristic plans has seriously complicated efforts for the limitation of the strategic arms race."[50] Western military leaders were generally happy with the decision. NATO commander Alexander Haig described the ALCM as an "attractive alternative" to the B-1. French General Georges Buis stated "The B-1 is a formidable weapon, but not terribly useful. For the price of one bomber, you can have 200 cruise missiles."[50]

Flight tests of the four B-1A prototypes for the B-1A program continued through April 1981. The program included 70 flights totaling 378 hours. A top speed of Mach 2.22 was reached by the second B-1A. Engine testing also continued during this time with the YF101 engines totaling almost 7,600 hours.[55]

Shifting priorities

[edit]

It was during this period that the Soviets started to assert themselves in several new theaters of action, in particular through Cuban proxies during the Angolan Civil War starting in 1975 and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. U.S. strategy to this point had been focused on containing Communism and preparation for war in Europe. The new Soviet actions revealed that the military lacked capability outside these narrow confines.[citation needed]

The U.S. Department of Defense responded by accelerating its Rapid Deployment Forces concept but suffered from major problems with airlift and sealift capability.[56] In order to slow an enemy invasion of other countries, air power was critical; however the key Iran-Afghanistan border was outside the range of the United States Navy's carrier-based attack aircraft, leaving this role to the U.S. Air Force.

During the 1980 presidential campaign, Ronald Reagan campaigned heavily on the platform that Carter was weak on defense, citing the cancellation of the B-1 program as an example, a theme he continued using into the 1980s.[57] During this time Carter's defense secretary, Harold Brown, announced the stealth bomber project, apparently implying that this was the reason for the B-1 cancellation.[58][verification needed]

B-1B program

[edit]

On taking office, Reagan was faced with the same decision as Carter before: whether to continue with the B-1 for the short term, or to wait for the development of the ATB, a much more advanced aircraft. Studies suggested that the existing B-52 fleet with ALCM would remain a credible threat until 1985. It was predicted that 75% of the B-52 force would survive to attack its targets.[59] After 1985, the introduction of the SA-10 missile, the MiG-31 interceptor and the first effective Soviet Airborne Early Warning and Control (AWACS) systems would make the B-52 increasingly vulnerable.[60] During 1981, funds were allocated to a new study for a bomber for the 1990s time-frame which led to developing the Long-Range Combat Aircraft (LRCA) project. The LRCA evaluated the B-1, F-111, and ATB as possible solutions; an emphasis was placed on multi-role capabilities, as opposed to purely strategic operations.[59]

In 1981, it was believed the B-1 could be in operation before the ATB, covering the transitional period between the B-52's increasing vulnerability and the ATB's introduction. Reagan decided the best solution was to procure both the B-1 and ATB, and on 2 October 1981 he announced that 100 B-1s were to be ordered to fill the LRCA role.[40][61]

In January 1982, the U.S. Air Force awarded two contracts to Rockwell worth a combined $2.2 billion for the development and production of 100 new B-1 bombers.[62] Numerous changes were made to the design to make it better suited to the now expected missions, resulting in the B-1B.[51] These changes included a reduction in maximum speed,[58] which allowed the variable-aspect intake ramps to be replaced by simpler fixed geometry intake ramps. This reduced the B-1B's radar cross-section which was seen as a good trade off for the speed decrease.[40] High subsonic speeds at low altitude became a focus area for the revised design,[58] and low-level speeds were increased from about Mach 0.85 to 0.92. The B-1B has a maximum speed of Mach 1.25 at higher altitudes.[40][63]

The B-1B's maximum takeoff weight was increased to 477,000 pounds (216,000 kg) from the B-1A's 395,000 pounds (179,000 kg).[40][64] The weight increase was to allow for takeoff with a full internal fuel load and for external weapons to be carried. Rockwell engineers were able to reinforce critical areas and lighten non-critical areas of the airframe, so the increase in empty weight was minimal.[64] To deal with the introduction of the MiG-31 equipped with the new Zaslon radar system, and other aircraft with look-down capability, the B-1B's electronic warfare suite was significantly upgraded.[40]

Opposition to the plan was widespread within Congress. Critics pointed out that many of the original problems remained in both areas of performance and expense.[65] In particular it seemed the B-52 fitted with electronics similar to the B-1B would be equally able to avoid interception, as the speed advantage of the B-1 was now minimal. It also appeared that the "interim" time frame served by the B-1B would be less than a decade, being rendered obsolete shortly after the introduction of a much more capable ATB design.[66] The primary argument in favor of the B-1 was its large conventional weapon payload, and that its takeoff performance allowed it to operate with a credible bomb load from a much wider variety of airfields. Production subcontracts were spread across many congressional districts, making the aircraft more popular on Capitol Hill.[67]

B-1A No. 1 was disassembled and used for radar testing at the Rome Air Development Center in the former Griffiss Air Force Base, New York.[68] B-1As No. 2 and No. 4 were then modified to include B-1B systems. The first B-1B was completed and began flight testing in March 1983. The first production B-1B was rolled out on 4 September 1984 and first flew on 18 October 1984.[69] The 100th and final B-1B was delivered on 2 May 1988;[70] before the last B-1B was delivered, the USAF had determined that the aircraft was vulnerable to Soviet air defenses.[71]

In 1996, Rockwell International sold most of its space and defense operations to Boeing,[72] which continues as the primary contractor for the B‑1 as of 2024.[1]

Design

[edit]

Overview

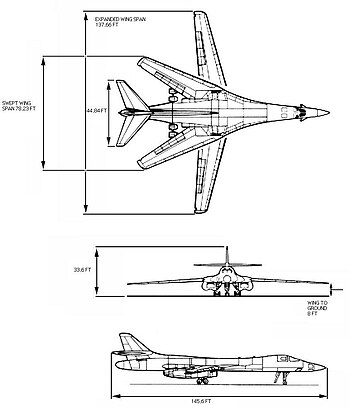

[edit]The B-1 has a blended wing body configuration, with variable-sweep wing, four turbofan engines, triangular ride-control fins and cruciform tail. The wings can sweep from 15 degrees to 67.5 degrees (full forward to full sweep). Forward-swept wing settings are used for takeoff, landings and high-altitude economical cruise. Aft-swept wing settings are used in high subsonic and supersonic flight.[73] The B-1's variable-sweep wings and thrust-to-weight ratio provide it with improved takeoff performance, allowing it to use shorter runways than previous bombers.[74] The length of the aircraft presented a flexing problem due to air turbulence at low altitude. To alleviate this, Rockwell included small triangular fin control surfaces or vanes near the nose on the B-1. The B-1's Structural Mode Control System moves the vanes, and lower rudder, to counteract the effects of turbulence and smooth out the ride.[75]

Unlike the B-1A, the B-1B cannot reach Mach 2+ speeds; its maximum speed is Mach 1.25 (about 950 mph or 1,530 km/h at altitude),[76] but its low-level speed increased to Mach 0.92 (700 mph, 1,130 km/h).[63] The speed of the current version of the aircraft is limited by the need to avoid damage to its structure and air intakes. To help lower its radar cross-section, the B-1B uses serpentine air intake ducts (see S-duct) and fixed intake ramps, which limit its speed compared to the B-1A. Vanes in the intake ducts serve to deflect and shield radar returns from the highly reflective engine compressor blades.[77]

The B-1A's engine was modified slightly to produce the GE F101-102 for the B-1B, with an emphasis on durability, and increased efficiency.[78] The core from this engine was subsequently used in several other engines, including the GE F110 used in the F-14 Tomcat, F-15K/SG variants and later versions of the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.[79] It is also the basis for the non-afterburning GE F118 used in the B-2 Spirit and the U-2S.[79] The F101 engine core is also used in the CFM56 civil engine.[80]

The nose-gear door is the location for ground-crew control of the auxiliary power unit (APU) which can be used during a scramble for quick-starting the APU.[81][82]

Avionics

[edit]

The B-1's main computer is the IBM AP-101, which was also used on the Space Shuttle orbiter and the B-52 bomber.[83] The computer is programmed with the JOVIAL programming language.[84] The Lancer's offensive avionics include the Westinghouse (now Northrop Grumman) AN/APQ-164 forward-looking offensive passive electronically scanned array radar set with electronic beam steering (and a fixed antenna pointed downward for reduced radar observability), synthetic aperture radar, ground moving target indication (GMTI), and terrain-following radar modes, Doppler navigation, radar altimeter, and an inertial navigation suite.[85] The B-1B Block D upgrade added a Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver beginning in 1995.[86]

The B-1's defensive electronics include the Eaton AN/ALQ-161A radar warning and defensive jamming equipment,[87] which has three sets of antennas; one at the front base of each wing and the third rear-facing in the tail radome.[88][89] Also in the tail radome is the AN/ALQ-153 missile approach warning system (pulse-Doppler radar).[90] The ALQ-161 is linked to a total of eight AN/ALE-49 flare dispensers located on top behind the canopy, which are handled by the AN/ASQ-184 avionics management system.[91] Each AN/ALE-49 dispenser has a capacity of 12 MJU-23A/B flares. The MJU-23A/B flare is one of the world's largest infrared countermeasure flares at a weight of over 3.3 pounds (1.5 kg).[92] The B-1 has also been equipped to carry the ALE-50 towed decoy system.[93]

Also aiding the B-1's survivability is its relatively low RCS. Although not technically a stealth aircraft, thanks to the aircraft's structure, serpentine intake paths and use of radar-absorbent material its RCS is about 1/50th that of the similar sized B-52. This is approximately 26 ft2 or 2.4 m2, comparable to that of a small fighter aircraft.[91][94][95]

The B-1 holds 61 FAI world records for speed, payload, distance, and time-to-climb in different aircraft weight classes.[96][97] In November 1993, three B-1Bs set a long-distance record for the aircraft, which demonstrated its ability to conduct extended mission lengths to strike anywhere in the world and return to base without any stops.[98] The National Aeronautic Association recognized the B-1B for completing one of the 10 most memorable record flights for 1994.[93]

Upgrades

[edit]

The B-1 has been upgraded since production, beginning with the "Conventional Mission Upgrade Program" (CMUP), which added a new MIL-STD-1760 smart-weapons interface to enable the use of precision-guided conventional weapons. CMUP was delivered through a series of upgrades:

- Block A was the standard B-1B with the capability to deliver non-precision gravity bombs.

- Block B brought an improved Synthetic Aperture Radar, and upgrades to the Defensive Countermeasures System and was fielded in 1995.[99]

- Block C provided an "enhanced capability" for delivery of up to 30 cluster bomb units (CBUs) per sortie with modifications made to 50 bomb racks.[100]

- Block D added a "Near Precision Capability" via improved weapons and targeting systems, and added advanced secure communications capabilities.[100] The first part of the electronic countermeasures upgrade added Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), ALE-50 towed decoy system, and anti-jam radios.[87][101][102]

- Block E upgraded the avionics computers and incorporated the Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser (WCMD), the AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) and the AGM-158 JASSM (Joint Air to Surface Standoff Munition), substantially improving the bomber's capability. Upgrades were completed in September 2006.[103]

- Block F was the Defensive Systems Upgrade Program (DSUP) to improve the aircraft's electronic countermeasures and jamming capabilities, but it was canceled in December 2002 due to cost overruns and delays.[104]

In 2007, the Sniper XR targeting pod was integrated on the B-1 fleet. The pod is mounted on an external hardpoint at the aircraft's chin near the forward bomb bay.[105] Following accelerated testing, the Sniper pod was fielded in summer 2008.[106][107] Future precision munitions include the Small Diameter Bomb.[108]

The USAF commenced the Integrated Battle Station (IBS) modification in 2012 as a combination of three separate upgrades when it realised the benefits of completing them concurrently; the Fully Integrated Data Link (FIDL), Vertical Situational Display Unit (VSDU) and Central Integrated Test System (CITS).[109] FIDL enables electronic data sharing, eliminating the need to enter information between systems by hand.[110] VSDU replaces existing flight instruments with multifunction color displays, a second display aids with threat evasion and targeting, and acts as a back-up display. CITS saw a new diagnostic system installed that allows crew to monitor over 9,000 parameters on the aircraft.[111] Other additions are to replace the two spinning mass gyroscopic inertial navigation system with ring laser gyroscopic systems and a GPS antenna, replacement of the APQ-164 radar with the Scalable Agile Beam Radar – Global Strike (SABR-GS) active electronically scanned array, and a new attitude indicator.[112] The IBS upgrades were completed in 2020.[109]

In August 2019, the Air Force unveiled a modification to the B-1B to allow it to carry more weapons internally and externally. Using the moveable forward bulkhead, space in the intermediate bay was increased from 180 to 269 in (457 to 683 cm). Expanding the internal bay to make use of the Common Strategic Rotary Launcher (CSRL), as well as utilizing six of the eight external hardpoints that had been previously out of use to keep in line with the New START Treaty, would increase the B-1B's weapon load from 24 to 40. The configuration also enables it to carry heavier weapons in the 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) range, such as hypersonic missiles; the AGM-183 ARRW is planned for integration onto the bomber. In the future the HAWC could be used by the bomber which, combining both internal and external weapon carriage, could conceivably bring the total number of hypersonic weapons to 31.[113][114][115]

Operational history

[edit]Strategic Air Command

[edit]The second B-1B, "The Star of Abilene", was the first B-1B delivered to SAC in June 1985. Initial operational capability was reached on 1 October 1986 and the B-1B was placed on nuclear alert status.[116][117] The B-1 received the official name "Lancer" on 15 March 1990. However, the bomber has been commonly called the "Bone"; a nickname that appears to stem from an early newspaper article on the aircraft wherein its name was phonetically spelled out as "B-ONE" with the hyphen inadvertently omitted.[2]

In late 1990, engine fires in two Lancers led to a grounding of the fleet. The cause was traced back to problems in the first-stage fan, and the aircraft were placed on "limited alert"; in other words, they were grounded unless a nuclear war broke out. Following inspections and repairs they were returned to duty beginning on 6 February 1991.[118][119] By 1991, the B-1 had a fledgling conventional capability, forty of them able to drop the 500-pound (230 kg) Mk-82 General Purpose (GP) bomb, although mostly from low altitude. Despite being cleared for this role, the problems with the engines prevented their use in Operation Desert Storm during the Gulf War.[71][120] B-1s were primarily reserved for strategic nuclear strike missions at this time, providing the role of airborne nuclear deterrent against the Soviet Union.[120] The B-52 was more suited to the role of conventional warfare and it was used by coalition forces instead.[120]

Originally designed strictly for nuclear war, the B-1's development as an effective conventional bomber was delayed. The collapse of the Soviet Union had brought the B-1's nuclear role into question, leading to President George H. W. Bush ordering a $3 billion conventional refit.[121]

After the inactivation of SAC and the establishment of the Air Combat Command (ACC) in 1992, the B-1 developed a greater conventional weapons capability. Part of this development was the start-up of the U.S. Air Force Weapons School B-1 Division.[122] In 1994, two additional B-1 bomb wings were also created in the Air National Guard, with former fighter wings in the Kansas Air National Guard and the Georgia Air National Guard converting to the aircraft.[123] By the mid-1990s, the B-1 could employ GP weapons as well as various CBUs. By the end of the 1990s, with the advent of the "Block D" upgrade, the B-1 boasted a full array of guided and unguided munitions.

The B-1B no longer carries nuclear weapons;[40] its nuclear capability was disabled by 1995 with the removal of nuclear arming and fuzing hardware.[124] Under provisions of the New START treaty with Russia, further conversions were performed. These included modification of aircraft hardpoints to prevent nuclear weapon pylons from being attached, removal of weapons bay wiring bundles for arming nuclear weapons, and destruction of nuclear weapon pylons. The conversion process was completed in 2011, and Russian officials inspect the aircraft every year to verify compliance.[125]

Air Combat Command

[edit]

The B-1 was first used in combat in support of operations in Iraq during Operation Desert Fox in December 1998, employing unguided GP weapons. B-1s have been subsequently used in Operation Allied Force (Kosovo) and, most notably, in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[40] The B-1 has deployed an array of conventional weapons in war zones, most notably the GBU-31, 2,000-pound (910 kg) JDAM.[40] In the first six months of Operation Enduring Freedom, eight B-1s dropped almost 40 percent of aerial ordnance, including some 3,900 JDAMs.[112] JDAM munitions were heavily used by the B-1 over Iraq, notably on 7 April 2003 in an unsuccessful attempt to kill Saddam Hussein and his two sons.[126] During Operation Enduring Freedom, the B-1 was able to raise its mission capable rate to 79%.[93]

Of the 100 B-1Bs built, 93 remained in 2000 after losses in accidents. In June 2001, the Pentagon sought to place one-third of its then fleet into storage; this proposal resulted in several U.S. Air National Guard officers and members of Congress lobbying against the proposal, including the drafting of an amendment to prevent such cuts.[71] The 2001 proposal was intended to allow money to be diverted to further upgrades to the remaining B-1Bs, such as computer modernization.[71] In 2003, accompanied by the removal of B-1Bs from the two bomb wings in the Air National Guard, the USAF decided to retire 33 aircraft to concentrate its budget on maintaining availability of remaining B-1Bs.[127] In 2004, a new appropriation bill called for some retired aircraft to return to service,[128] and the USAF returned seven mothballed bombers to service to increase the fleet to 67 aircraft.[129]

On 14 July 2007, the Associated Press reported on the growing USAF presence in Iraq, including reintroduction of B-1Bs as a close-at-hand platform to support Coalition ground forces.[130] Beginning in 2008, B-1s were used in Iraq and Afghanistan in an "armed overwatch" role, loitering for surveillance purposes while ready to deliver guided bombs in support of ground troops as required.[131][132]

The B-1B underwent a series of flight tests using a 50/50 mix of synthetic and petroleum fuel; on 19 March 2008, a B-1B from Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, became the first USAF aircraft to fly at supersonic speed using a synthetic fuel during a flight over Texas and New Mexico. This was conducted as part of an USAF testing and certification program to reduce reliance on traditional oil sources.[133] On 4 August 2008, a B-1B flew the first Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod equipped combat sortie where the crew successfully targeted enemy ground forces and dropped a GBU-38 guided bomb in Afghanistan.[106]

In March 2011, B-1Bs from Ellsworth Air Force Base attacked undisclosed targets in Libya as part of Operation Odyssey Dawn.[134]

With upgrades to keep the B-1 viable, the USAF may keep it in service until approximately 2038.[135] Despite upgrades, a single flight hour needs 48.4 hours of repair. The fuel, repairs, and other needs for a 12-hour mission cost $720,000 (~$982,308 in 2023) as of 2010.[136] The $63,000 cost per flight hour is, however, less than the $72,000 for the B-52 and the $135,000 of the B-2.[137] In June 2010, senior USAF officials met to consider retiring the entire fleet to meet budget cuts.[138] The Pentagon plans to begin replacing the aircraft with the B-21 Raider after 2025.[139] In the meantime, its "capabilities are particularly well-suited to the vast distances and unique challenges of the Pacific region, and we'll continue to invest in, and rely on, the B-1 in support of the focus on the Pacific" as part of President Obama's "Pivot to East Asia".[140]

In August 2012, the 9th Expeditionary Bomb Squadron returned from a six-month tour in Afghanistan. Its 9 B-1Bs flew 770 sorties, the most of any B-1B squadron on a single deployment. The squadron spent 9,500 hours airborne, keeping one of its bombers in the air at all times. They accounted for a quarter of all combat aircraft sorties over the country during that time and fulfilled an average of two to three air support requests per day.[141] On 4 September 2013, a B-1B participated in a maritime evaluation exercise, deploying munitions such as laser-guided 500 lb GBU-54 bombs, 500 lb and 2,000 lb JDAM, and Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASM). The aim was to detect and engage several small craft using existing weapons and tactics developed from conventional warfare against ground targets; the B-1 is seen as a useful asset for maritime duties such as patrolling shipping lanes.[142]

Beginning in 2014, the B-1 was used against the Islamic State (IS) in the Syrian Civil War.[143][144] From August 2014 to January 2015, the B-1 accounted for eight percent of USAF sorties during Operation Inherent Resolve.[145] The 9th Bomb Squadron was deployed to Qatar in July 2014 to support missions in Afghanistan, but when the air campaign against IS began on 8 August, the aircraft were employed in Iraq. During the Battle of Kobane in Syria, the squadron's B-1s dropped 660 bombs over 5 months in support of Kurdish forces defending the city. This amounted to one-third of all bombs used during OIR during the period, and they killed some 1,000 ISIL fighters. The 9th Bomb Squadron's B-1s went "Winchester"–dropping all weapons on board–31 times during their deployment. They dropped over 2,000 JDAMs during the six-month rotation.[144] B-1s from the 28th Bomb Wing flew 490 sorties where they dropped 3,800 munitions on 3,700 targets during a six-month deployment. In February 2016, the B-1s were sent back to the U.S. for cockpit upgrades.[146]

Air Force Global Strike Command

[edit]As part of a USAF reorganization announced in April 2015, all B-1s were reassigned from Air Combat Command to Global Strike Command (GSC) in October 2015.[147]

On 8 July 2017, the USAF flew two B-1s near the North Korean border in a show of force amid increasing tensions, particularly in response to North Korea's 4 July test of an ICBM capable of reaching Alaska.[148]

On 14 April 2018, B-1s launched 19 JASSM missiles as part of the 2018 bombing of Damascus and Homs in Syria.[149][150][151] In August 2019, six B-1Bs met full mission capability; 15 were undergoing depot maintenance and 39 under repair and inspection.[152]

In February 2021, the USAF announced it will retire 17 B-1s, leaving 45 aircraft in service. Four of these will be stored in a condition that will allow their return to service if required.[153][154]

In March 2021, B-1s deployed to Norway's Ørland Main Air Station for the first time. During the deployment, they conducted bombing training with Norwegian and Swedish ground force Joint terminal attack controllers. One B-1 also conducted a warm-pit refuel at Bodø Main Air Station, marking the first landing inside Norway's Arctic Circle, and integrated with four Swedish Air Force JAS 39 Gripen fighters.[155][156]

On 2 February 2024, the U.S. deployed two B-1Bs to strike 85 terrorist targets in seven locations in Iraq and Syria as part of a multi-tiered response to the killing of three U.S. troops in a drone attack in Jordan.[157]

Variants

[edit]

- B-1A

- The B-1A was the original B-1 design with variable engine intakes and Mach 2.2 top speed. Four prototypes were built; no production units were manufactured.[129][158]

- B-1B

- The B-1B is a revised B-1 design with reduced radar signature and a top speed of Mach 1.25. It is optimized for low-level penetration. A total of 100 B-1Bs were produced.[158]

- B-1R

- The B-1R was a 2004 proposed upgrade of existing B-1B aircraft.[159] The B-1R (R for "regional") would be fitted with advanced radars, air-to-air missiles, and new Pratt & Whitney F119 engines (from the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor). This variant would have a top speed of Mach 2.2, but with 20% shorter range.[160] Existing external hardpoints would be modified to allow multiple conventional weapons to be carried, increasing overall loadout. For air-to-air defense, an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar would be added and some existing hardpoints modified to carry air-to-air missiles.[159]

Operators

[edit]

The USAF had 45 B-1Bs in service as of July 2024.[161]

United States

United States-

- United States Air Force

-

- Strategic Air Command 1985–1992

- Air Combat Command 1992–2015

- Air Force Global Strike Command 2015–present

- 7th Bomb Wing – Dyess AFB, Texas

- 9th Bomb Squadron 1993–present

- 13th Bomb Squadron 2000–2005

- 28th Bomb Squadron 1994–present

- 337th Bomb Squadron 1993–1994

- 28th Bomb Wing – Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota

- 34th Bomb Squadron 2002–present

- 37th Bomb Squadron 1986–present

- 77th Bomb Squadron 1985–95, 1997–2002

- 53d Test and Evaluation Group – Nellis AFB, Nevada

- 337th Test and Evaluation Squadron (Dyess AFB, Texas) 2004–present

- 57th Wing – Nellis AFB, Nevada

- 77th Weapons Squadron (Dyess AFB, Texas) 2003–present

- 96th Bomb Wing – Dyess AFB, Texas

- 337th Bomb Squadron 1985–1993

- 338th Combat Crew Training Squadron 1986–1993

- 4018th Combat Crew Training Squadron 1985–1986

- 319th Bomb Wing – Grand Forks AFB, North Dakota 1987–1994

- 366th Wing – Mountain Home AFB, Idaho 1994-1996 (geographically separated at Ellsworth AFB, SD) 1997–2002

- 34th Bomb Squadron

- 384th Bomb Wing – McConnell AFB, Kansas 1987–1994

- 28th Bomb Squadron

- 7th Bomb Wing – Dyess AFB, Texas

- Air National Guard

- 116th Bomb Wing – Robins AFB, Georgia 1996–2002

- 128th Bomb Squadron

- 184th Bomb Wing – McConnell AFB, Kansas 1994–2002

- 127th Bomb Squadron

- 116th Bomb Wing – Robins AFB, Georgia 1996–2002

- Air Force Flight Test Center – Edwards AFB, California

- 412th Operations Group 1989–1992

- 412th Test Wing 1992–present

- 6510th Test Wing 1974–1989

- 6519th Flight Test Squadron

Aircraft on display

[edit]

- B-1A

- 74-0160 – Wings Over the Rockies Museum at the former Lowry Air Force Base in Denver, Colorado.[162]

- 76-0174 – Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum near Ashland, Nebraska. This aircraft has conventional ejection seats and other features used on the B-1B variant.[163]

- B-1B

- 83-0065 Star of Abilene – Dyess Linear Air Park at Dyess Air Force Base, Texas. This was the first aircraft delivered to the U.S. Air Force. Dyess AFB is home to one of two active Air Force B-1B wings.[citation needed]

- 83-0066 Ole Puss – Heritage Park at Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho with wheels in the wells.[citation needed]

- 83-0067 Texas Raider – South Dakota Air and Space Museum at Ellsworth Air Force Base, South Dakota. Ellsworth AFB is home to one of two active Air Force B-1B wings.[164]

- 83-0068 Spuds – Reflections of Freedom Air Park at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, Kansas, a former Air Force and Air National Guard B-1B base.[citation needed]

- 83-0069 Silent Penetrator – Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins, Georgia, a former Air National Guard B-1B base. This aircraft was the sixth B-1 produced, and was delivered to the 96th Bomb Wing at Dyess AFB, Texas on 13 March 1986. This aircraft arrived at Robins AFB in September 2002. Robins AFB was previously home to one of two Air National Guard B-1B wings.[165] Renamed Midnight Train From Georgia by April 2015

- 83-0070 7 Wishes – Hill Aerospace Museum at Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah.[166]

- 83-0071 Spit Fire – near the main gate at Tinker Air Force Base, Oklahoma. This aircraft was one of two that suffered an in-flight engine failure in 1990 that led to grounding of the fleet.[citation needed]

- 84-0051 Boss Hawg – National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB near Dayton, Ohio. It is displayed in the museum's Cold War Gallery, and replaces the B-1A (76-0174) formerly on display.[167]

Accidents and incidents

[edit]

The Aviation Safety Network lists 15 accidents from 1984 to 2024 in which 11 B-1s were lost and a total of 12 crew members were killed.[168] An April 2022 maintenance fire damaged another.[169] Among the incidents:

- On 29 August 1984, B-1A (serial number (74-0159) crashed because of a loss of control during a test flight over the Mojave Desert. The center of gravity was well aft of the limit due to fuel transfer error. Two crew members survived and a Rockwell test pilot was killed.[170]

- On 28 September 1987, B-1B (84–0052) from the 96th Bomb Wing, 338th Combat Crew Training Squadron, Dyess AFB, crashed near La Junta, Colorado, while flying on a low-level training route. This was the only B-1B crash with six crew members aboard. The two crew members in jump seats, and one of the four crew members in ejection seats perished. An impact—thought to be a bird strike on a wing's leading edge—severed fuel and hydraulic lines on one side of the aircraft, while the other side's engines functioned long enough to allow the crew to eject. The B-1B fleet was later modified to protect these supply lines.[171][172]

- In October 1990, while flying a training route in eastern Colorado, B-1B (86-0128) from the 384th Bomb Wing, 28th Bomb Squadron, McConnell AFB, experienced an explosion as the engines reached full power without afterburners. Fire on the aircraft's left was spotted. The No. 1 engine was shut down and its fire extinguisher was activated. The accident investigation determined that the engine had suffered catastrophic failure, engine blades had cut through the engine mounts, and the engine had detached from the aircraft.[171]

- In December 1990, B-1B (83-0071) from the 96th Bomb Wing, 337th Bomb Squadron, Dyess AFB, Texas, experienced a jolt that caused the No. 3 engine to shut down and activate its fire extinguisher. This event, coupled with the October 1990 engine incident, led to a 50-plus-day grounding of B-1Bs that were not on nuclear alert status. The problem was traced to problems in the first-stage fan, and all B-1Bs were equipped with modified engines.[171]

- On 30 November 1992, B-1B (86-0106) crashed 300 feet below a 6,500-foot ridgeline during a night sortie 36 miles south-southwest of Van Horn, Texas. All four crew died in the crash.[173]

- On 19 September 1997, B-1B (85-0078) crashed near Alzada, Montana, during a daytime training flight. The aircraft struck the ground due to an excessive sink rate when the crew was performing a defensive maneuver. All four crew were killed.[174]

- On 12 December 2001, while supporting Operation Enduring Freedom, B-1B (86-0114) flying from the British Air Base, Diego Garcia, crashed into the Indian Ocean about 30 miles north of the island. All four crew members ejected safely and were rescued in good condition after two hours in a warm, calm sea. The pilot, Capt. William Steele, later told reporters the aircraft had not been hit by hostile fire but had suffered "multiple malfunctions" that made it impossible to handle.[175][176]

- In September 2005, a B-1B (85-0066) from Ellsworth AFB landed at Andersen AFB and caught fire while exiting the runway. Cause was determined to be failure of brakes on the right main landing gear when leaking hydraulic fluid came in contact in a "hot brakes" situation. The resulting fire damaged the right wing, nacelle, aircraft structure, and right main landing gear assembly. The aircraft was repaired at Andersen over a three-year period with many parts obtained from retired B-1Bs in storage at Davis–Monthan AFB, Arizona. The aircraft returned to flight in 2008.[177]

- On 19 August 2013, B-1B (85-0091) crashed during a routine training mission in Broadus, Montana, 170 miles southeast of Billings, Montana, because of a fuel leak and explosion that damaged a wing during a wing sweep. All four crew ejected safely.[178]

- On 20 April 2022, a fire broke out on B-1B (85-0089) of the 7th Bomb Wing, assigned to Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, that was undergoing maintenance on the main ramp. The fire damaged the No. 1 engine, the left nacelle, and the wing of the aircraft. Falling debris injured an airman. The estimated cost of damage is $14.944 million.[179]

- On 4 January 2024, B-1B (85-0085) assigned to Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota crashed while attempting to land at the installation while on a training mission. At the time of the crash, visibility was poor and temperatures freezing. The four aircrew on board ejected safely.[180] The total loss for the crash was reported as $456,248,485 (2024).[181]

Specifications (B-1B)

[edit]

Data from USAF Fact Sheet,[93] Jenkins,[182] Pace,[63] Lee[87]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 (Aircraft Commander, Pilot, Offensive Systems Officer, and Defensive Systems Officer)

- Length: 146 ft (45 m)

- Wingspan: 137 ft (42 m)

- Swept wingspan: 79 ft (24 m) swept

- Height: 34 ft (10 m)

- Wing area: 1,950 sq ft (181 m2)

- Airfoil: NACA69-190-2

- Empty weight: 192,000 lb (87,090 kg)

- Gross weight: 326,000 lb (147,871 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 477,000 lb (216,364 kg)

A B-1B flying over the Pacific Ocean - Powerplant: 4 × General Electric F101-GE-102 afterburning turbofan engines, 17,390 lbf (77.4 kN) thrust each dry, 30,780 lbf (136.9 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 721 kn (830 mph, 1,335 km/h) at altitude of 40,000 ft (12,000 m); 608 kn (1,126 km/h) at 200–500 ft (61–152 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.25

- Range: 5,100 nmi (5,900 mi, 9,400 km) with weapon load of 37,000 lb (16,800 kg). Max range is 6,500 nmi (12,000 km).[183]

- Combat range: 2,993 nmi (3,444 mi, 5,543 km)

- Service ceiling: 60,000 ft (18,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 5,678 ft/min (28.84 m/s)

- Wing loading: 167 lb/sq ft (820 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.38 at gross weight

Armament

- Hardpoints: 6 external hardpoints for ordnance[c] with a capacity of 50,000 pounds (23,000 kg), with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles:

- Bombs:

- Mk-82 air inflatable retarder (AIR) general purpose (GP) bombs[188]

- Mk-82 low drag general purpose (LDGP) bombs[189]

- Mk-62 Quickstrike sea mines[190]

- Mk-84 general-purpose bombs

- Mk-65 naval mines[191]

- CBU-87/89/CBU-97 Cluster Bomb Units (CBU)[d]

- CBU-103/104/105 Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser (WCMD) CBUs

- GBU-31 JDAM GPS guided bombs (Mk-84 GP or BLU-109 warhead)[e]

- GBU-38 JDAM GPS guided bombs (Mk-82 GP warhead)[f]

- GBU-38 JDAM (using rotary launcher mounted multiple ejector racks)[192]

- GBU-54 LaserJDAM (using rotary launcher mounted multiple ejector racks)[192]

- GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb GPS guided bombs[g] (not fielded on B-1 yet)

- Missiles:

- Bombs: 3 internal bomb bays for 75,000 pounds (34,000 kg) of ordnance.[184]

Avionics

- 1× AN/APQ-164 forward-looking offensive passive electronically scanned array radar

- 1× AN/ALQ-161 radar warning receiver and defensive jamming equipment

- 1× AN/ASQ-184 defensive management system

- 1× Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod (optional)[193][194]

Weapons loads

[edit]| Bomb rack & stores[195] | Bay 1 | Bay 2 | Bay 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | ||||

| CBM 2,816 to 3,513 lb (1,277 to 1,593 kg) |

1 | 1 | 1 | |

|

28 | 28 | 28 | 84 |

| Conventional | ||||

| SECBM (CBM w/ TMD upgrade) 2,816 lb (1,277 kg) empty |

1 | 1 | 1 | |

|

10 | 10 | 10 | 30 |

| GBU-38 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 15 |

| Multi-purpose | ||||

| MPRL 1,300 to 2,055 lb (590 kg) |

1 | 1 | 1 | |

|

8 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| Mk-65 naval mines | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

|

8 | 8 | 8 | 96 or 144 |

| Multi-purpose (mixed) | ||||

| MPRL (MER upgrade)[196] |

1 | 1 | 1 | |

| * GBU-38, GBU-32, GBU-31 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 36 |

| GBU-38 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 48 |

| Ferry/range extension | ||||

| Fuel tank 2,975 gal (11,262 L)[197] |

1 | 1 | 1 | 3 9,157 gal (34,663 kg)[198] |

| Nuclear (uniform; out of use) | ||||

|

1 | 1 | 1 | |

| B28[199] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

|

8 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| Nuclear (mixed)(out of use)[200] | ||||

|

1 | |||

| AGM-86B | Small fuel tank 8 |

8 | ||

| Bomb rack & stores | Fwd stations 1–2 | Int. stations 3–6 | Aft stations 7–8 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear (out of use) | ||||

| Dual-pylon | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Single-pylon | 2 | |||

|

2×2 | 2×2 + 2 | 2×2 | 14[h] |

| Conventional (uniform) | ||||

| Mk-82 | 2×6 | 2×6 + 2×6 | 2×6 | 44 |

| Targeting[201] | ||||

| Pylon 884 lb (400 kg) |

1 (right station) | |||

| Sniper XR targeting pod | 1 (right station) | 1 440 lb (200 kg) | ||

| Ferry/range extension[198][202] | ||||

| Fuel tank each 923 gal (3,494 L) |

2 | 2 | 2 | 6 5,538 gal (20,963 L) |

Notable appearances in media

[edit]See also

[edit]- Political positions of Ronald Reagan

- ASALM, Advanced Strategic Air-Launched Missile

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military electronics of the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ Production totals: B-1A: 4; B-1B: 100

- ^ The name "Lancer" was only applied to the B-1B variant in 1990.[2]

- ^ Use for weapons restricted by arms treaties.[106][185]

- ^ As per B-1B Weapons Loading Checklist T.O. 1B-1B-33-2-1CL-13

- ^ both Mk-84 general purpose and BLU-109 penetrating bombs

- ^ As per B-1B Weapons Loading Checklist T.O. 1B-1B-33-2-1CL-12 Section 3.4 (Only six each in forward and intermediate bays and three each in the aft bay)

- ^ 96 if using four-packs, 144 if using 6-packs. This capability has not yet been fielded on the B-1

- ^ Restricted to 12 under SALT II.[200]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "B-1B Lancer". Air Force. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 1999, p. 67.

- ^ Cohen, Rachel (24 September 2021). "Farewell, Bones: Air Force finishes latest round of B-1B bomber retirements". Air Force Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer". Air Force. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Losey, Stephen (24 September 2021). "Last of 17 Retired B-1s Sent to Boneyard as Air Force Preps for B-21s". Military.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "USAF to Retire B-1, B-2 in Early 2030s as B-21 Comes On-Line". Air Force Magazine. 11 February 2018. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b c Schwartz 1998, p. 118.

- ^ Rich, Ben and Leo Janos. Skunk Works. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-316-74300-3.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 1999, p. 21.

- ^ "May 1960 – The U-2 Incident. – Soviet and American Statements." Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Keesing's Record of World Events, Volume 6, 1960.

- ^ a b Spick 1986, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz 1998, p. 119.

- ^ "NASA-CR-115702, B-70 Aircraft Study Final Report, Vol. I, p. I-38." Archived 12 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine NASA, 1972.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Knaack 1988, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 256.

- ^ Gunston 1978, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Taylor, Gordon. "Subsonic Low Altitude Bomber" Archived 19 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base ASD-TDR-62-426, June 1962.

- ^ Pace 1998, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Knaack 1988, pp. 575–576.

- ^ Casil 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 576.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 575.

- ^ Hibma, R.A; Wegner, E.D (12–14 May 1981). "The Evolution of a Strategic Bomber". 16th Annual Meeting and Technical Display. AIAA 16th Annual Meeting and Technical Display. Long Beach, CA. doi:10.2514/6.1981-919. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Pace 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Knaack 1988, pp. 576–577.

- ^ "B-1A page." Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d Knaack 1988, pp. 576–578.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1999, pp. 23–26.

- ^ "AN/APQ – Airborne Multipurpose/Special Radars". Designation-systems.net. 1 July 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Knaack 1988, p. 579.

- ^ a b c Pace 1998, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kocivar, Ben. "Our New B-1 Bomber – High, Low, Fast, and Slow." Archived 2 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine Popular Science, Volume 197, Issue 5, November 1970, p. 86.

- ^ a b Knaack 1988, p. 584.

- ^ "Rockwell International history 1970–1986." Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Boeing. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ a b Sorrels 1983, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lee 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Whitford 1987, p. 136.

- ^ Schefter, Jim. "The Other Story About The Controversial B-1." Archived 8 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine Popular Science, Volume 210. Issue 5, May 1977, p. 112.

- ^ Spick 1986, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 586.

- ^ Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1975–76, John W.R.Taylor, ISBN 0531032507, p. 439

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 44.

- ^ Willis, David K. "Japan's scrutiny of Soviet jet jars détente." Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor, 16 September 1976. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Donald 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 590.

- ^ a b c d "Carter's Big Decision: Down Goes the B-1, Here Comes the Cruise." Archived 1 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine Time, 11 July 1977. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ a b Withington 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Pace 1999, pp. 20–27.

- ^ Sorrels 1983, p. 23.

- ^ Belcher, Jerry. "Dropping B-1 Would Bring World War III, Dornan Says." Archived 2 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 11 June 1977.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Moore, John Leo (1980). U.S. Defense Policy: Weapons, Strategy, and Commitments. Congressional Quarterly. pp. 65, 79. ISBN 978-0-87187-158-9. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Reagan, President Ronald. "Reagan's Radio Address to the Nation on Foreign Policy." Archived 17 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine presidentreagan.info. 20 October 1984.

- ^ a b c Schwartz 1998, p. 120.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Douglas D. "IB81107, "Bomber Options for Replacing B-52s." Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, via Digital Library, UNT, 3 May 1982. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Jumper, John P. "Global Strike Task Force: A Transforming Concept, Forged by Experience." Archived 12 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Aerospace Power Journal 15, no. 1, Spring 2001, pp. 30–31. Originally published by Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, 2001.

- ^ Coates, James. "Reagan approves B-1, alters basing for MX." Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 3 October 1981. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Pace 1998, p. 64.

- ^ a b Spick 1986, p. 28.

- ^ Casil 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Germani, Clara, ed. "Former defense chief raps B-1 bomber plan." Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor, 21 September 1981. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "B-1 Lancer | PDF | Aerospace Engineering | Aircraft". Retrieved 24 April 2024 – via Scribd.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, pp. 70–74.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "B-1B Background Information." Archived 26 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine Boeing. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d Dao 2001, p. 1

- ^ Peltz, James (2 August 1996). "Rockwell to Sell Off Space, Defense Divisions to Boeing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ Withington 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Knaack 1988, p. 587.

- ^ Wykes, J. H. "AIAA-1972-772, B-1 Structural Mode Control System." Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 9 August 1972. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 60.

- ^ Spick 1986, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Spick 1987, p. 498.

- ^ a b "F110 Family." Archived 28 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine GE Aviation. Retrieved 25 January 2010

- ^ "CFM delivers 20,000th engine". Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine CFM International. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Spick 1986, p. 44.

- ^ Pace 1998, p. 44.

- ^ "Ch4-3". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Jovial to smooth U.S. Air Force shift to Ada. (processing language)". Defense Electronics. 1 March 1984.

- ^ "AN/APQ-164 B-1B Radar". Archived 12 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Northrop Grumman. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Withington 2006, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b c Lee 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Spick 1986, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 106.

- ^ "AN/ALQ-153 Missile Warning System". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b Skaarup 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Humphries, J. A. and D. E. Miller. "AIAA-1997-2963: B-1B/MJU-23 flare strike test program." Archived 20 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, 33rd, Seattle, Washington, 6–9 July 1997. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d "B-1B USAF fact sheet". Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2017.. U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Radar Cross Section Measurements (8–12 GHz) of Magnetic and Dielectric Microwave Absorbing Thin Sheets" (PDF). Sbfisica.org.br. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Cunningham, Jim. "The New Old Threat: Fighter Upgrades and What They Mean for the USAF", p. 7. Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Illinois State University, 3 December 1997.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. Appendix E.

- ^ "History – B-1 Lancer Bomber." Archived 23 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Boeing. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Dorr 1997, p. 224.

- ^ "Aerospaceweb.org | Aircraft Museum - B-1B Lancer". aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b Skaarup 2002, p. 19.

- ^ "Boeing Completes Block E Avionics Upgrade of B-1 Bomber Fleet." Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 4 December 1998. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Adams, Charlotte. "Building Blocks to Upgrade to B-1B." Archived 29 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Avionics Magazine, 1 August 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Boeing 2006 Block E Upgrades." Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 27 September 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ "Block F Upgrades." US Air Force, 21 January 2003. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Hernandez, Jason. "419th FLTS demonstrates Sniper pod capability." Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force, 23 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Pate, Capt. Kristen. "Sniper ATP-equipped B-1B has combat first". Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2008. US Air Force, 11 August 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ La Rue, Nori. "B-1 Sniper pod aims to hit summer target." Archived 8 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force, 4 June 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Wicke, Russell. (5 October 2006). "ACC declares small diameter bomb initially operational". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ^ a b Mullan, Ron (24 September 2020). "B-1B Integrated Battle Station modification completed". tinker.af.mil. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Maull, Lisa and Forrest Gossett. "Boeing B-1 Upgraded With Fully Integrated Data Link Completes 1st Flight." Archived 3 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Boeing, 13 August 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "B-1B Systems Engineer Explains How IBS Makes Future Bomber Upgrades Easier". 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b Air Force Begins Massive B-1B Overhaul Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Defensetech.org, 21 February 2014

- ^ B-1B bomber modified to carry hypersonic missiles Archived 29 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. New Atlas. 9 September 2019.

- ^ Hypersonic weapons could give the B-1 bomber a new lease on life Archived 8 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine. Defense News. 16 September 2019.

- ^ AFGSC Eyes Hypersonic Weapons for B-1, Conventional LRSO Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Air Force Magazine. 7 April 2020.

- ^ Pace 1998, pp. 62, 69.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 83.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 116.

- ^ B-1 aircrew logbook entry.

- ^ a b c Withington 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Dao 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Scott, Ed. "JDAM Course Ushers B-1 Students Into New Era". Program Manager, 1 November 1999. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ Withington 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Jenkins 1999, p. 141.

- ^ Pawlyk, Oriana. "START Lanced the B-1's Nukes, But the Bomber Will Still Get New Bombs". Military.com. Military Advantage. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Withington 2006, pp. 75–76.

- ^ "B-1 bomber's final flight." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Arizona Star, 21 August 2002. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ Klamper, Amy. "Lawmakers look after home military installations." Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine govexec.com, 25 June 2004. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ a b Mehuron, Tamar A. "USAF Almanac: Facts and Figures" (data as of 30 September 2004). Archived 6 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, May 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J. "Air Force Quietly Building Iraq Presence." Archived 10 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine commondreams.org, 14 July 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Wicke, Tech. Sgt. Russell, "B-1 performs as never envisioned after 20 years." Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force, 17 April 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Door 2010, pp. 40–45.

- ^ Bates, Matthew. "B-1B achieves first supersonic flight using synthetic fuel". Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2008. Air Force News, 20 March 2008.

- ^ "Ellsworth Airmen join Operation Odyssey Dawn." Archived 2 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Rapid City Journal, 29 March 2011.

- ^ Hebert, Adam J. "The 2018 Bomber and Its Friends." Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Air Force magazine, October 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ Shachtman, Noah. "The Air Force Needs a Serious Upgrade," Archived 8 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Brookings Institution, 15 July 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ Axe, David. "Why Can't the Air Force Build an Affordable Plane?" Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic, 26 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Budget cutting axe may fall on the U.S. bomber force." Archived 2 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Reporter News. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "New B-21 bomber named 'Raider': U.S. Air Force". Reuters. 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

The stealth B-21, the first new U.S. bomber of the 21st century, is part of an effort to replace the USAF's aging B-52 and B-1 bombers, though it is not slated to be ready for combat use before 2025.

- ^ Brook, Tom Vanden. "B-1 bomber mission shifts from Afghanistan to China, Pacific." Archived 4 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine USA Today, 11 May 2012.

- ^ "The 24/7 Bone Over Afghanistan." Archived 17 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Strategypage.com, 15 August 2012.

- ^ U.S. Air Force tests B-1B Lancer bomber for maritime environment & anti-ship missions Archived 23 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Navyrecognition.com, 19 September 2013

- ^ "Air Force fighters, bombers conduct strikes against ISIL targets in Syria". United States Air Force. 23 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b Everstine, Brian (23 August 2015). "Inside the B-1 crew that pounded ISIS with 1,800 bombs". Air Force Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "A-10 Performing 11 Percent of Anti-ISIS Sorties". Defensenews.com, 19 January 2015.

- ^ "B-1 bombers pulled from ISIS fight". CNN. 21 February 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "AF realigns B-1, LRS-B under Air Force Global Strike Command" Archived 23 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force, 20 April 2015.

- ^ Tomlinson, Lucas (8 July 2017). "2 US Air Force B-1 bombers fly near North Korean border in show of force". Fox News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Trevithick, Tyler Rogoway and Joseph (13 April 2018). "United States, France, And UK Begin Air Strikes on Syria (Updating Live)". The Drive. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Brad Lendon (14 April 2018). "Weapons the US, UK and France used to target Syria". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Pawlyk, Oriana (17 April 2018). "US May Ramp Up Buy of the Missile That Just Made Combat Debut in Syria". Military.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ Gady, Franz-Stefan (7 August 2019). "Only 6 of 61 US Air Force B-1B Strategic Bombers Are Fully Combat-Ready". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Jennings, Gareth (19 February 2021). "USAF begins B-1B retirements". janes.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "AFGSC begins retirement of B-1 aircraft, paving way for B-21". United States Air Force. 18 February 2021. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Samövning med amerikanskt bombflyg" (in Norwegian). Försvarsmakten. 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Utvikler samarbeid". Forsvaret (in Norwegian). 9 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Analysis: What to make of the US strikes against pro-Iranian militias in Iraq and Syria". CNN. 2 February 2024. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ a b Donald 1997, p. 723.

- ^ a b Lewis, Paul; Simonsen, Erik (2004), "Offering Unique Solutions for Global Strike Force.", All Systems Go, vol. 2, no. 2, Boeing, archived from the original on 12 December 2007, retrieved 8 October 2009 – via Internet Archive

- ^ Hebert, Adam J. "Long-Range Strike in a Hurry." Archived 6 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, November 2004. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "rage resurrected from boneyard". 14 July 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ "B-1A Lancer/74-160." Archived 20 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Wings Over The Rockies Air & Space Museum. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "B-1A Lancer/76-174." Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Strategic Air Command Museum. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer/83-0067." Archived 7 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine South Dakota Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer/83-0069." Archived 2 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Museum of Aviation. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer/83-0070." Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Hill Aerospace Museum. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer/84-0051." Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer Accidents and Incidents". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "Accident Rockwell B-1B Lancer 85-0089". Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "74-0159". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 1999, pp. 114–116.

- ^ "84-0052". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "86-0106". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "85-0078". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Stout, David (12 December 2001). "Crew Rescued After B-1 Bomber Crashes into Indian Ocean". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "86-0014". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Andersen, Tinker rebuild B-1". 3 December 2007.

- ^ "85-0091". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "United States Air Force Aircraft Accident Investigation Board Report: B-1B, T/N 85-0089" (PDF). United States Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "B-1 bomber crashes at South Dakota Air Force base, crew ejects safely". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "85-0085". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Jenkins 1999

- ^ "B-1". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Boeing: B-1B Lancer". Boeing. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "ACQWeb" Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine START I: Letter on B-1

- ^ Mizokami, Kyle "The B-1 Bomber Has a New Mission" Archived 4 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Popular Mechanics, 22 August 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "B-1B Lancer | The B-1 Bomber Might Carry Hypersonic Missiles". Popular Mechanics. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ As per B-1B Weapons Loading Checklist T.O. 1B-1B-33-2-1CL-8

- ^ As per B-1B Weapons Loading Checklist T.O. 1B-1B-33-2-1CL-7 (changed from 84 to 81 due to fit issues on 28X CBM with new tailkits)

- ^ "Bad to the B-ONE." Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, March 2007, p. 63. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1999, p. 142.

- ^ a b Rivezzo, Charles V. "337 TES demonstrates ability to triple B-1 payload". Archived 12 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine. 7th Bomb Wing Public Affairs, USAF, 7 April 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. "The Big Squeeze." Archived 25 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, Journal of the Air Force Association, Volume 90, Issue 10, October 2007. ISSN 0730-6784.

- ^ Kessler, Capt. Carrie L. "B-1 crews conduct TWF test; receive pod spin-up." Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Print News Today, 29 February 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ a b "The Weapons File "[permanent dead link] Air Armament Center

- ^ "B-1B Lancer upgrade will triple payload" Archived 14 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force News, 11 April 2011

- ^ "Uncovering the Rockwell B-1B Lancer" Willy Peeters, Daco Publications, ISBN 978-9080674776, 2006

- ^ a b Technical Order 00-105E-9 Revision 11, 1 February 2006.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Modern U.S. Military Weapons", Berkley Hardcover; 1st edition, 1 August 1995, ISBN 978-0425147818

- ^ a b "The B-1B Bomber and Options for hancements" Archived 14 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Congressional Budget Office, August 1988

- ^ "Sniper ATP-equipped B-1B has combat first" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force News, 11 August 2008

- ^ "NA 95-1210 B-1B Fact Book" Archived 6 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. North American Aircraft, Rockwell International, 20 July 1995. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Casil, Amy Sterling (2003). The B-1 Lancer. New York: Rosen. ISBN 0-8239-3871-9.

- Dao, James. "Much-Maligned B-1 Bomber Proves Hard to Kill." The New York Times, 1 August 2001.